If you were to take a moment and think about what the moniker ‘progressive’ actually means in relation to its influence on music, you might come up with a dozen different ways in which it can be competently applied. Some of these may be based on the simple mechanics of time changes and structural variation, and others may lean toward a more analytical approach on the aspects of music that truly progress the medium in a meaningful way. While there are various discussions on whether progressive rock – and by extension, progressive metal – is/are truly ‘progressive’, the nomenclature for such does in fact exist in a myriad of forms and in reference to a slew of musical ideals. So in a attempt to make sense of just what this means for the music we enjoy and to explore the benign etymology of the word’s impact, let’s attempt to loosely define the inherently indefinable over the course of this multi-part series.

Perspective

In nearly all forms of the definition for progress and progressive, the concept of forward momentum is noted. A continuous and ongoing movement towards an unspecified ‘something’. Be it a definite goal or simply the autotelic ideal of improvement and change for its own sake. So what does this mean for music? In truth, this description itself is inherently more attuned to the idea of avant garde than it is applicable to our common use of prog, but where does that leave us?

Perhaps the perspective of a contemporary group immersed in everything that is prog can help us get started. Here’s what the guys from Mile Marker Zero have to say about the genre:

“‘Progressive music’ seems to exist in two sorts of ways. One is in the ‘traditional’ sense, the post Sergeant Peppers idealistic, ambitious rock style of music coming mainly from the UK, which combined the ethos of the day often with virtuosic instrumental passages (i.e. Yes, King Crimson, Genesis etc). This era of bands – and subsequent eras that were spawned by these groups – are typically referred to as ‘Prog’ music. However, the second definition of ‘progressive music’ is a bit more of a mindset and approach. Progressive music in this sense is one that continuously evolves… not bound by too many rules, structures, or sonic templates, and evolving over time. This kind of approach can be seen in the modern day by acts such as Radiohead, Tool, and Steven Wilson most clearly.

We’ve found that many groups who play ‘prog’ now are playing with definition #1 in mind, and tend to avoid definition #2. Over time, the blueprint of definition #1 can make your music become stagnant unless one incorporates elements from definition #2.”

Looking a little father back, we get a fairly comprehensive definition of the genre of progressive rock from Jerry Lucky in his book The Progressive Rock Files, noting a more systematic listing of general structural elements. It touches on length, passage differentiation, instrument variety, compositions, and much more. While it works in a superficial sense to categorize music into a neat little box, it leaves a lot of important pieces to the puzzle still on the table. Kevin Holm-Hudson attempts to expand on this idea in his book Progressive Rock Reconsidered, by compiling a number of thoughtful explorations on the historical context and ideological perspectives of the early progenitors in the genre. If you enjoy music history in any form, it’s a worthy read that delves into some of the greats like Yes, ELP, King Crimson, Roger Waters, and Rush.

Put simply, these discussions are important, and none of my continued meanderings are meant to pull away from these perspectives. By delving into the philosophy and traditions of progressivism in music, as well as the continued discussions in future parts of this series, I only hope to provide an alternative perspective that adds to the discourse, and perhaps show you a few interesting new bands along the way. If you’re looking for more of a primer on the genre, I recommend the New Yorker’s look at the brands persistence over the decades and the episode of ‘Prog Metal’ from Banger Films Metal Evolution documentary series. Past this point I will assume you are up to speed.

Philosophy

Modern interpretations of Hegelian dialectics proposes a pendulum of meanings and ideologies that swings via thesis and antithesis, resolving in synthesis. While Hegel’s perspectives were focused predominantly on the wider sociological landscape of major shifts in human history (and theories being avidly argued against in terms of defining a true antithesis), the core of this idea on discourse – or a dialect – to sublation is one that rears its head in the world of music at both micro and macro levels numerous times over the course of the medium’s history.

In more general terms, the dialect involves an initial movement (let’s say hair metal in the 80’s), followed by a secondary movement that flows in opposition to the first (grunge and the wave of popular music that drew taught against concepts like guitar solos and flashy, polished imagery). These two are then reconciled and synthesized into a singular stream drawing from the wells of both initial ideas (the mixture of these schools of thought in the bandcamp/youtube age of music). This is what drives the core of sublation, or aufheben: to abolish, to preserve, and to transcend.

Adjusting our lens back to progressive music, we can view this ‘progression’ of the genre in literal terms of moving forward by synthesizing oppositions into a new paradigm. You can see this in how the traditional vein of Dream Theater-esque bands and it’s modern, aggressive counterparts that focus on songwriting over technique, were at the forefront of what bred the likes of BTBAM and Persefone, or take a smaller scale look into the compositions within In the Court of the Crimson King to see this sublation in a microcosm. Moreover, this also works on an ideological level regarding the push, pull, and eventual combination of musical elements on a more grand scale, modulating the pillars that house the giants that bands today stand on the shoulders of.

But while Hegelian dialectics provides a distinct lens to view prog over time, the true core of the styles identity lies in the idea of synthesis in all forms. Synthesis of musical concepts, instrument variety, disparate and parallel elements, and more. The acts that truly stand out in the genre are those that blend pieces from other places into a unique whole. More on how this idea next time, for now let’s touch on the seeds that bloomed into the touchstone of future synthesis.

Pillars of Progs Past and Present

Before diving into the minutia of what birthed the genre, I’d like to acknowledge the sociopolitical, cultural, and ideological touchstones that ignited the fires of music’s overall development, prog notwithstanding. While those won’t be present in our current discussion, you can learn about the influence of counterculture on English prog in Edward Macan’s Rocking The Classics and an interesting article on rock as performance here. For our purposes, I want to touch on the four main appeals that led to the need for music that was more complex and varied than was previously presented: theatrics, virtuosity, concepts, and emotions.

Theatrics

Popular music in the west, at its core, relies on a very tried and true structure; one that creates potential limits on the types of expressions one can portray. There are certainly ways to incorporate narrative and a stronger sense of variation among the pieces that make up a composition within these boundaries, but it is little wonder why a trend of eschewing these foundations grew in the wake of new creative directions. The ebb and flow of a multi part composition and the demands of a complex and emotive story pine for freedom in articulation.

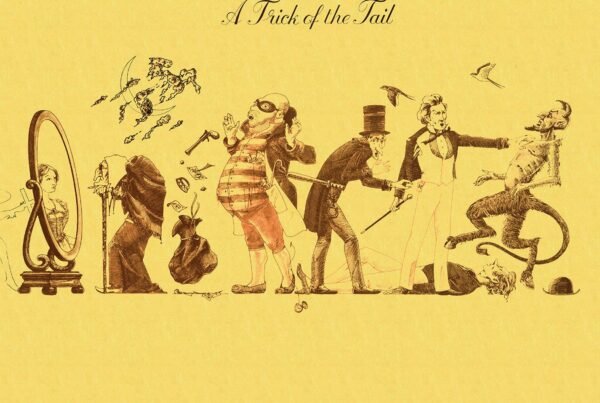

This theatrical mentality is present in a number of the early greats and is a central driving force to many of the most revered albums within the genre. One needs only to look at the likes of Genesis, Jethro Tull, and Pink Floyd to understand how. The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, Thick as a Brick, and The Wall all contain an air of indistinct nature in direction, and their narratives are the single most salient aspect directing the flow of musical possibilities. There are overt elements of a classic rock mentality within the scaffolding of the compositional text, but the defining moments that elevate the music (ie. the innocence and characterization in “Mother” or the naivety present in The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway’s titular track, for example) are these more story driven elements. There is an attempt here to do more than simply write songs for the sake of making music, and in the implementation of text-typing (or audio-narrative consistency) the needs of the song expand the scope of the performances therein.

That is not to say that a song for music’s sake cannot also pull on this thread. There is a lot of contention around Queen’s inclusion as a prog rock progenitor, but this element is very clearly present in a number of tracks that tread the line of having progressive influences. Drama, from a tragedy/drama perspective (not the sanguine depictions associated with the term), characterizes every tonal change and character progression in the omnipresent “Bohemian Rhapsody”, along with many others within their extensive catalogue.

From Fear of a Blank Planet to Sleeping in Traffic, 2112 to Aquarius, this narrative driven, theatrical push to tell a story through lyrics and music in equal parts continues to be a driving force in the most well received progressive records to this day. It, along with the subsequent divulgence on technical ability, seem to be the most prominent forces that lead to the need to expand genres.

Virtuosity

There was a time when a simple catchy melody was at the forefront of not only what people wanted to hear, but also what drew people into the (at the time) modern music industry as a whole. It wasn’t long before we had individuals with exceptional talent who grew to lament this mentality and wanted to, again, push the boundaries of the music they created. We often take for granted the Petrucci like speeds and Minnemann-esque complexity of patterns present nowadays in most progressive metal music, but this progression of technical ability is one that grew steady over time.

We’ve come a long way from the days of Rainbow, Deep Purple, and Yes, Blackmore and Banks. Bands and musicians that, not all of which may be considered progressive, act as a competent origin for the types of technical divulgences that define the instrumental moments in modern prog. Pushing the envelope of what could be done – as was done with Banks’ finger tapping, for instance – led to a generation of musicians who wanted to further this ability, to expand the limits of technical prowess until the seams tore away. We see the likes of Rush, followed by Steve Vai, Dream Theater, and many more. Bands and musicians that continue to wander through virtuosic principles, crafting foundations that echo in the music of today.

This dynamic of songwriting through the presentation of physical ability within the songwriting structure itself is what bred the instrumental meanderings that pervades modern prog, pit stops on the path to a traditional resolution, earning their progressive moniker through ability alone. While a counterpoint anthesis exists in the form of more simplistic prog that focuses on crafting through writing, we seem to (in many contemporary cases) have sublimated into a paradigm of balancing virtuosity and songwriting.

Concepts

Perhaps the least prominent of the pillars, conceptual manifestations in prog remain a necessary support to indulge progressive tendencies where theatrics, virtuosity, and emotions are less prevalent. What do I mean by conceptual manifestations? I’m talking about music that is thematically consistent and abstractly crafted with a singular vision. The easy way to see this is as a concept album, though many examples of non-narratively driven works exist that still contain a defining threadline from which ideas blossom into something a bit more complex than a set of non-interconnected tracks.

Two relatively recent examples that come to mind when thinking of this are The Raven That Refused to Sing and Fortress. Steven Wilson’s offering touches on a number of supernatural stories, disconnected from each other in a linear fashion, but held together by theming and tone. Protest the Hero similarly have a set of tracks bound together by mythology and worship in a way only bassist Arif can aptly describe: “Fortress isn’t so much an album, as it is a symphony with many parts and movements that flow into one another, making it both a cohesive unit and a collection of songs that can be listened to in a group or as individuals. While Fortress doesn’t follow the rigid concept of 2005’s Kezia, it’s still thematic.”

In tying things together thematically or conceptually, certain structural motives and writing devices get used, often leading to a work that is more musically complex and a package that is more thoughtfully received. Recurring instrumental motifs and reprised lyrics punctuate the individual tracks, combining to elevate the whole into more than the sum of its parts.

Emotions

Let’s take a step back and return to the aforementioned Pink Floyd and the song that follows our previously mentioned one on The Wall, “Goodbye Blue Sky”. It most definitely fits within the realm of a theatrical narrative, but more than that, it also preys on the emotions of its lead character and those of the listener. Oppressive, yet hopeful chording, a striking contrast of arrangements, and a haunting set of lyrics, create an environment that is fearful yet comforting at the same time. It elicits a powerful emotional response from the listener, but to do so it plays with expectations in a way unique from simple structural changes. Through the composition and instrumentation itself, it crafts a somber and dismal tone the likes of which the like of Simon and Garfunkel had only touched on prior. It’s tone and voice alone convey complexity through simplicity, offering depth to a tried and true framework.

While “Goodnight Blue Sky” may still bear the marks of a traditional structure, often a tendency toward emotional portrayals leads to changes in the expectations of the song itself. To stay consistent, let’s use another Floyd track. “Welcome to the Machine” uses long form repetition in melody, highly experimental sound design for the time, and generously put, a ‘loose’ traditional structure of verse-chorus, verse-chorus, etc. In fact, you could argue the same for a vast majority of their catalogue, which aside from the narrative slant at times, nearly exclusively uses atmosphere and emotive responses to craft music that is undeniably progressive, without virtuosic showmanship or a swath of unusual time changes.

A more modern example of this would be British six-piece Anathema. Listen to any of the tracks off of We’re Here Because We’re Here or Weather Systems and you will immediately notice an appeal to emotions, rather than a focus on musicianship. Despite the term progressive often being paraded around in discussion on the band, virtually none of the telltale signs Jerry Lucky described above can be attributed to their sound. As Cavanagh puts it, “Progressive music to this band is The Beatles, Radiohead, Pink Floyd and bands like that and these are bands that you don’t hear massive, elaborate show off parts like guitar solos. What you hear are songs.”

What leads listeners to draw the conclusion that progressive is an appropriate descriptor for the band is in how the emotional pallet influences the subtle moments on their albums, such as the extended quiet introspections, or the build to catharsis of the more recognizable singles. This approach creates a fairly noticeable, yet difficult to pinpoint or assess, change in conveyance. A change that garners the need for a unique descriptor. A progression that incorporates and pushes forward.

Abstraction

Here we are at the end of part one, and yet the lines between what is and isn’t prog seem to be washing in and out of reach like the tide. While we likely won’t find something definitive on the matter, the ideas above provide a potential lens to view why progressive elements in music became necessary, and how this had been conveyed thus far, leading into how the moniker has changed over time.

Not all of these pillars are necessary for music to be considered prog, nor do having these elements automatically earn you this branding. These are simply the cores of which that birthed the need to expand the type of music that existed prior to this point. Problems of conveyance that required a unique solution in presentation, if you will. The solution being the expansion of how we define music, the sublation of ideas into a new whole, and the momentum of progress leading the medium forward.

Let’s be honest, this was a bit of a long ride so far. If you’ve made it here, then thank you for your time. Take a break and come back to join us for part two, where we look at what makes prog what it is, and how the meaning of prog has changed since.