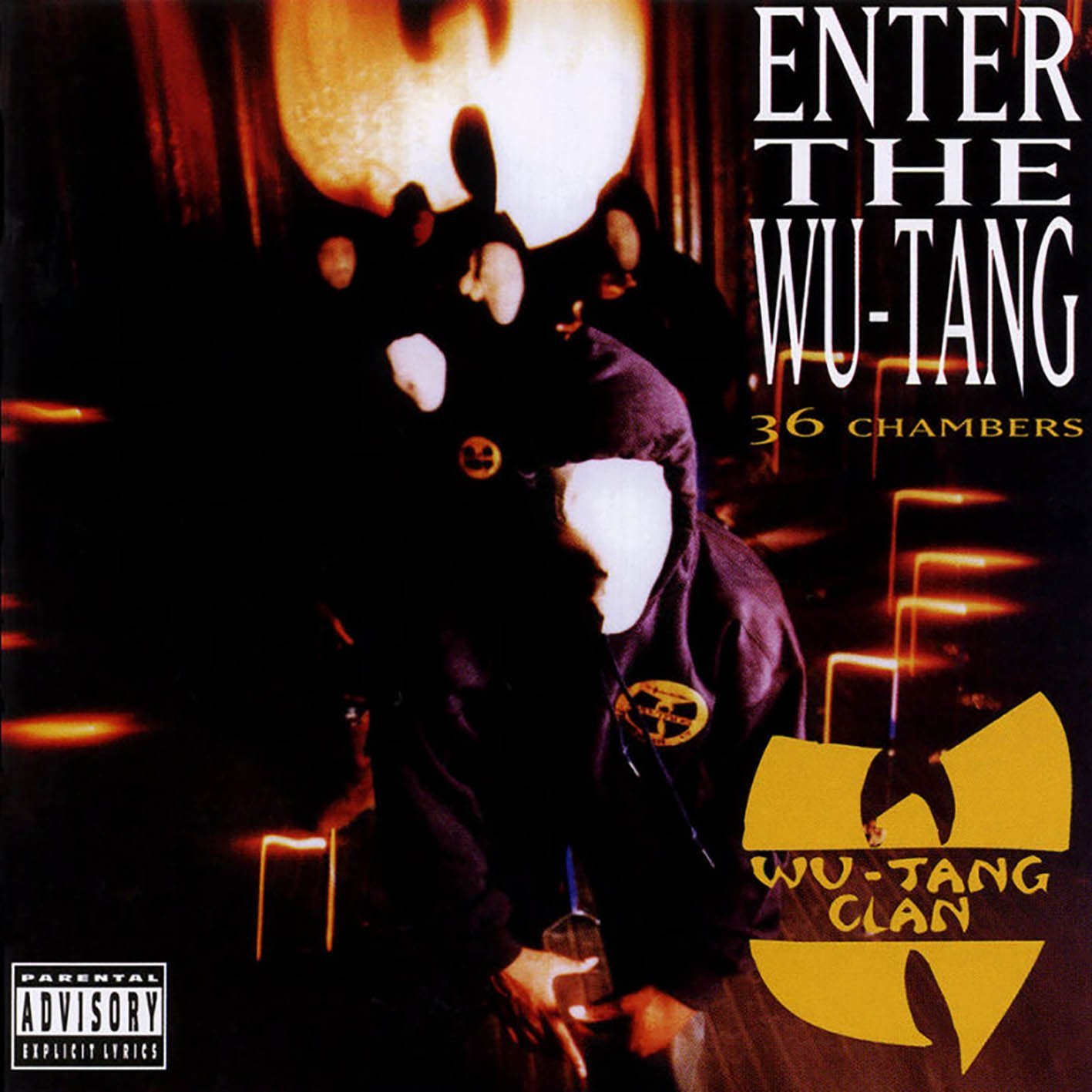

Wu-Tang Clan ain’t nothing to fuck with, and in this iteration of A Scene In Retrospect, I’m going to tell you exactly why their 1993 debut album, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) one of the best hip-hop albums ever. We near its 27th birthday on November 9, so there’s no better time to do so. No one else wanted to bring the motherfucking ruckus with me, so you just get me loving all over it for 1,700 words. Enjoy! Remember to press play on the songs as you read for optimal ambiance.

David Rodriguez (that's me!)

1993 was a banner year for hip-hop. This was around the time hip-hop was starting to get really mean. Onyx dropped their absolutely antagonistic album Bacdafucup, Mobb Deep came out with Juvenile Hell, and Esham birthed a horrorcore staple in KKKill the Fetus. Between all of this, nine dudes from Staten Island, New York were coming together with one common goal: change the game forever. They were the RZA, the GZA, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, Inspectah Deck, U-God, Ghostface Killah, the Method Man, Raekwon the Chef, the Masta Killa – the motherfucking Wu-Tang Clan.

Even with the confident demeanor that comes with being a hard-boiled New Yorker, not even the Wu could could probably foresee how much of a mark they’d leave on the scene. Think about it – while they might have existed without Wu-Tang coming first, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) precedes Nas‘ Illmatic, Biggie‘s Ready to Die, and Jay-Z‘s Reasonable Doubt. It’s commonly accepted that the success of hip-hop’s more hardcore edge that emerged from New York during this time (and other places as would soon become evident) is indebted to them.

They also kept New York in the forefront of minds when considering consistent hot beds of rap. The West Coast was winding the hell up with the success and controversy of artists like NWA and their members, Snoop Dogg, and the whole of the G funk movement coming out of Southern Cali. Texas and other areas of the South were about to jump off, if not already had, but I digress. The point is, Wu-Tang might have been for the children, but more importantly, they were for the musical and cultural legacy born in New York and wasn’t going anywhere. And they did it by keeping it real, raw, and rugged as fuck.

I’m not going to front like I grew up with this album – I was only four when it dropped on November 9, 1993, same day as the perfect A Tribe Called Quest album, Midnight Marauders. I didn’t get hip to Wu-Tang until “Gravel Pit” became a hit around 2000 and I discovered channels like MTV and VH1 who played the song’s absolutely bananas video often. Some years later, I’m hearing seminal tracks like “C.R.E.A.M.”, “Protect Ya Neck”, and “Can It Be All So Simple” on the radio – rarely since they were a bit old by this point, but they still proved to be earworms and a great introduction (along with other aforementioned artists) into hip-hop’s golden age.

All right, enough old head history lesson, let’s talk 36 Chambers. The primary strength for this album is apparent from one listen alone: cohesion. The way the airy soul and distinctively East Coast sample-based production clashes with the hard-boiled and brutish lyrics from all members, or the nonet‘s (I just wanted to use that word) chemistry and effortless building off each other’s energy like a perpetual boulder rolling down the big-ass staircase on 167th Street in the Bronx.

Entering the 36 chambers is a lot like stepping into a nighttime street corner cypher. You sense the smoke in the air, intermingling with your exhaled breath in the bitter New York cold, a gang of dudes in a circle, nodding heads while a beatboxer does his thing with someone stepping into the center about to rip shit up with precise, diamond-cut raps. As much as it is an exercise of skill and superiority within it, it’s also a boisterous act of bonding and brotherhood, forming solidarity against any and all comers.

From the group’s name to the film samples that flank songs, martial arts and Eastern influence runs deeps. Using dialogue and audio from cult films like Shaolin and Wu Tang and Ten Tigers from Kwangtung, the whole aesthetic feels like a natural precursor to how modern rappers would similarly use anime and video game samples or themes to color their art. It doesn’t feel hackneyed or even harmfully appropriative – it’s a bunch of genuine fans envisioning themselves and their crew as the toughest killers this side of Shaolin, throwing torso-breaking lyrical jabs, using vocal flow to flip freely around their opponents, and taking the term ‘punchline’ to its literal, logical conclusion – right to your dome.

From RZA’s opening line of ‘bring da motherfuckin’ ruckus‘ on, you guessed it, “Bring Da Ruckus”, to the his final reminder to ‘protect ya neck‘ on “Conclusion”, there’s an unbridled rowdiness. Bars are packed with braggadocio, rough gems of street knowledge, promises (not threats) of certain violence, and rampant shit-talking – for GZA’s second verse on “Clan In Da Front”, that’s a little too literal:

‘You become so pat as my style increases

What’s that in your pants? Ahh, human feces!

Throw your shitty drawers in the hamper

Next time, come strapped with a fuckin’ Pamper’

As demonstrated succinctly on “Intermission” (typically attached to the backend of “Can It Be All So Simple” as an outro), every single rapper has their place and specialty. In my own words, Ol’ Dirty Bastard is as inimitable as he is eccentric and untamed, Inspectah Deck is consistently one of the most lyrically dense on the records, Method Man is surgical with a distinct voice that literally hasn’t changed in 30 years, RZA produces all the tracks and jumps on the mic occasionally to attack from both sides, and Ghostface Killah (my favorite if you wondered) is the charismatic full lyrical package offering up combo blows as well as slick-ass storytelling.

Everything just has a grit you can’t shake. From the dusty sampling – aided by a now very distinct, dark ’90s style of production – to the combative lyrics, it’s not an experience that could be called safe in any regard. It embodies the unpredictable energy of New York’s boroughs, just as liable to rend upon you an ass kicking as it is a chilled-out drive with the top down as the unforgettable piano sample of The Charmels‘ “As Long as I’ve Got You” as heard in “C.R.E.A.M.” plays.

There’s nothing incredibly complex about the way Wu approaches hip-hop. The perceived effortlessless of the album betrays the grand execution that went into it all, but, especially with hindsight, it’s just a really, really solid hip-hop album by a bunch of pals that couldn’t be bothered to play by mainstream’s rules. This is partly what made 36 Chambers so encroaching and intimidating. The other part was making songs like “Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthin’ ta F’ Wit”, “Protect Ya Neck”, or “Shame on a Ni**a”, the latter of which was even… questionably covered in part by System Of A Down. Its horn samples and bouncy mood allowed ODB to lay down some quotables like ‘Burn me, I get into shit, I let it out like diarrhea/Got burned once, but that was only gonorrhea,’ with Method Man and RZA pulling up first to exact a galactic beatdown with river-like flow and razor-sharp bars. Let’s not forget Meth’s comically torturous intro to his eponymous song where he and Raekwon trade outlandish ways to bring the pain, outdoing each other and making friends laugh being the only goals.

You can’t be fierce at all times though – sometimes you have to cool out and reflect on the tough times overcame. That’s where gems like “Can It Be All So Simple” and “Tearz” come in. The former track is a melancholic joint featuring Raekwon and Ghostface Killah on verses that focus on childhood struggles and big dreams. The Chef almost gets nostalgic with his verse:

‘Ignorant and mad young, wanted to be the one

‘Til I got blaow, blaow, blaow! – felt one

Yeah, my pops was a fiend since 16

Shootin’ that ‘that’s that shit!’ in his bloodstream

That’s the life of a grimy, real-life crimey

And ni**as know that habit’s behind me‘

Cold realities rub shoulders with what the young men saw for themselves when they got older. Keep in mind, the ages of the members around this time were mid-twenties, which makes their childhood not a far cry from then, and their stories and lyrics that much more cutting and tragic. Ghostface laments this tone expertly:

‘I want to have me a phat yacht

And enough land to go and plant my own sess crops

But for now, it’s just a big dream

‘Cause I find myself in a place where I’m last seen

My thoughts must be relaxed, be able to maintain

‘Cause times is changed and life is strange

The glorious days is gone and everybody’s doin’ bad

Yo, mad lives is up for grabs

Brothers passin’ away, I gotta make wakes

Receivin’ all types of calls from upstate’

This level of realness, rooted in experiences all too common for fucked over and disenfranchised people, goes all the way back to Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five‘s “The Message“, but with Wu-Tang, there was conflicting visions. On one side is a sepia-tinted introspection on a hard youth that built each of the nine men, and on the other was a way out; to leave the unforgiving land of Shaolin (how Staten Island was referred to in the Wu mythos) and get that coveted cream in order to facilitate a better life. It’s a vision that came true for the group (to varying degrees – Ol’ Dirty Bastard died of a drug overdose in 2004) and it all started with 36 Chambers.

As I hear that lovely piano sample from “C.R.E.A.M.”, I can’t help but be reflective on my own life. It was nothing like the members of Wu-Tang‘s lives, but that’s the power of music. Even from the start, the group had a natural talent for being evocative, acerbic, and tougher than leather, with all respects to Run-DMC. No matter what ethnicity claims them, or what other career paths they may take, their mark was undeniably left on hip-hop and New York simply by virtue of being themselves, and that’s what it’s all about. To this day, they’re doing their thing – dropping new music as a group and solo artists, flipping their classics in new and awesome ways, and being the hardest rappers from Shaolin. Everything is temporary, but Wu-Tang is truly forever. If you’ve gone this long without entering the 36 chambers, there’s no time like the present. Just protect your neck.

And don’t forget to diversify your bonds.

What are your thoughts on/experiences with Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers)? Are you a fan of Wu-Tang Clan, and if so, what’s your favorite album of theirs or their members’ solo efforts? Do you have any records you’d like to recommend for inclusion in A Scene In Retrospect? Leave it all in the comments if you feel like sharing!