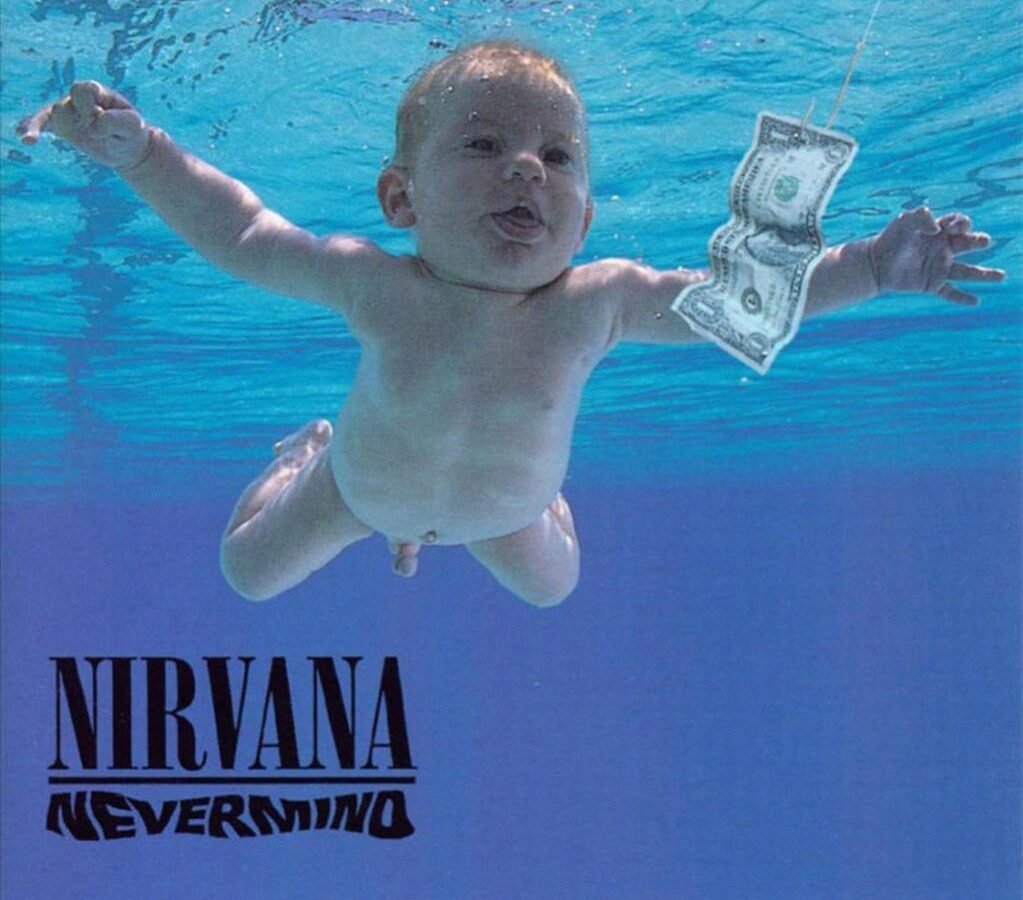

Much has been said about Nirvana and their towering Nevermind album over the three decades since its release – so much so that one might rightfully question what to add to the narrative, what superlatives or honors to bestow upon this record that it hasn’t garnered elsewhere already. So, six days after what would’ve been Kurt Cobain’s 55th birthday, we’ve decided to just go personal with it, talking about a massive, unrepeatable success story in music history within the confines of our own lives.

Landon Turlock

Content warning: This piece includes mentions of mental illness and depression. If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal ideation, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

I am turning 28 in a couple of weeks. I’d like to say that it’s being 27 that makes me think of Kurt Cobain at the age he died, but it’s not that commonality alone. It’s also the recognition of the fact that at 27, and at many ages before it, I did not see myself making it to 28. Instead, if I’m honest, I often imagined myself meeting a similar end to the songwriter behind Nirvana’s Nevermind, the subject of today’s discussion.

I don’t know how to write about Nevermind as an album for a lot of reasons. I imagine that more literal and virtual ink has been spilled about this record than the vast majority of records in history – what could I possibly add to the conversation? It also seems a little bit self-important to critique one of the best selling and most critically acclaimed albums of all time. And, most difficult for me, is the fact that Nevermind is not really a collection of songs for me as much as it is a part of me – how do I write about something so meaningful to me in any way that isn’t anything other than an uncomfortably intimate look into the life of some stranger on the Internet for whoever reads this? I don’t know if I can, but maybe we’ll start with the music.

I have no idea how it felt to hear “Smells Like Teen Spirit” on mainstream radio when it dropped in 1991. But I imagine that it was probably the rawest and most angsty song that had been heard by such a wide audience at that time. That’s what still sticks out to me about Nevermind, despite the decades I’ve spent listening to it – it’s probably the heaviest and grittiest pop album that has ever been made. Songs like “Territorial Pissings” or “Stay Away” or, especially, “Endless, Nameless” place raging punk and metal alongside acoustic tracks and pop anthems in a way that is maybe deliberately uncomfortable, but somehow not disparate – all of these tracks feel like different looks at the same picture, or all reflections on the same themes of loss, heartbreak, pain, and apathy.

When I was 12 and first discovered Nirvana by way of some guitar magazine transcription of “Lithium”, I’d never really heard music with those themes in a way that I really connected with. Sure, I was listening to Green Day, Metallica, Iron Maiden, and Black Sabbath, but their music had a veneer and pretense that Nirvana seemed to avoid. This music felt like it knew me and my early mental illness diagnosis, my social anxiety, and what it felt like to be bullied and excluded. It found a way to match what was going on in my head back then. That connection to Nevermind has only grown as I have.

But that connection has also changed. A song like “Polly”, despite Cobain and co.’s best intentions, brought poison into the world that I only later understood and I think they came to regret. Elsewhere, songs I underestimated have become new favourites – “On A Plain” and “Something In The Way” mean something to me now, in my late 20s, that they did not or could not mean to me when I was a preteen. The simple four-word (maybe five if we count ‘yeah’) chorus of “Something In The Way” gave me some kind of a life raft to hold onto last year when the undertow was particularly strong. I don’t know what was in the way for Cobain when he sang that song, and maybe I don’t need to – it’s a gift of Cobain’s to sing lyrics that may not be understandable while still being intensely relatable. I knew what was in the way for me, and I can’t say that this song or Nevermind as a whole made me feel better, but it helped me to feel understood and like I wasn’t alone.

Having music that helped me not to feel alone helped me take steps to ensure that I wasn’t alone in other facets of my life either. I reached out to my partner, my family, my friends, and my boss. I went back to therapy again. I got on meds again. And I’m the best I’ve been in a long time, not because of albums like Nevermind, but also not without them. I’ll make it to 28.

Inter

There were a couple of reasons why I was particularly interested in covering Nirvana‘s Nevermind for A Scene In Retrospect. For once, the more selfish approach: my relationship with the band and this album in particular, and how it evolved during the years serves as an interesting example for my own musical identity. Second, the phenomenon of popularity being a disservice for a piece of art. Last but no least, the album itself. A collection of songs, containing one of the most popular rock songs ever made. An interesting journey’s upon us.

So what does this albums means to me? I remember that a plethora of people around me wore Nirvana merch when I was teenager. Shirts, hoodies, patches, you name it. And I fucking hated it. With all my teeny insecurities, I hated those superficial people who tried to be ‘rock’ or ‘alternative’ or ‘grunge’ with the first row of merch in every mail order. Did they even know that Nirvana had other songs than “Smells Like Teen Spirit”? I doubted it. I didn’t even care for Nirvana that much, but the way of cultural appropriation hurt my world in ways only a teenager with a narrow horizon can understand. Me being pissed off by those ‘posers’ and realizing Nirvana was just ‘one of those bands people pretend to like as an accessory’ prevented any serious involvement from my side besides equally superficial disdain.

I look back with twisted nostalgia to these days, jealous about juvenile naiveté and glad about the shards of old man wisdom that I gained from being over 30. During the years, my curiosity for all kinds of music raised, my prejudices faded (at least a bit), and I discovered grunge as a fascinating genre. And while I still don’t care for Pearl Jam, I have a sweet spot for the other three of the Big Four of grunge, namely Soundgarden, Alice In Chains, and Nirvana. I love Soundgarden‘s dabbling in more psychedelic and trippy territory, appreciate Alice In Chains‘ vibing into more metal and stoner rock, and adore Nirvana for their peerless songwriting and drenching their music in punk and garage rock. I still feel that a lot of people belittle Nirvana for their popularity, like I did when I was younger. Their popularity is being a disservice to the band, so to speak.

Ignoring the not so smooth transition into the second point I want to talk about, I kind of wish that Nirvana would be closer to the level of cultural standing the other big grunge bands are. Sure, Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, and Alice In Chains are big names, but Nirvana is on a whole other level. The history of the band, Kurt Cobain as a cultural figure, Dave Grohl’s present popularity, and the whole romanticizing of the struggling rockstar, collapsing under the limelight of success kind of overshadow how good this band really was. It’s paradoxical, because one reason people are not that interested in Nevermind anymore are people constantly telling them how good this album is. By the way, Nevermind is really. Fucking. Good.

Let’s end my ramblings about this album with a bunch of reasons why I love Nevermind. I love that the tempo and the attitude of “In Bloom” feels like the whole song was dragged through mud. The pulse of that song is just so incredibly addictive, which makes “In Bloom” one of the best songs the band has ever done. The simple efficiency of the overly present 4-chords-patterns throughout the album really shines in the stripped down “Polly”, with iconic, yet disturbing lyrics and drowning in Cobain’s unique charisma. Staring into the abyss which is “Something In The Way”, getting sucked into its depressive and dark nature, showcasing some very interesting production choices.

The merits of Nevermind are plentiful and very immersive, and I had a lot of fun listening to the whole album while writing this text. I hope it tickles you to hit play on the album and think to yourself: ‘Yeah, that’s really. Fucking. Good.‘