Fainting Dreams strips away the rawness of its usual sound to house greatly increased emotional resonance at the core of an acutely personal, elegantly relayed story of finding yourself.

Release date: October 31, 2025 | Zegema Beach Records/Softseed Records | Facebook | Instagram | Bandcamp

Please be aware that this review is for an album centered around religious trauma, abuse, and transphobia suffered by the artist and thus speaks pretty candidly about those topics in ways some might find triggering, up to and including references to suicide.

You can be anything. This is something we grew up hearing all the time. Firefighter, doctor, astronaut, president – no matter how lofty, it was more important to stoke the embers of children’s imagination, to plant the seeds of dreams, than it was to be realistic at the time. The longer a kid can go without facing the realities and limitations of capitalistic society, the better, because the moment you do is the death of innocence. For some people though, the struggles of reality come in different forms and sooner than expected.

I’m out of my element as I stare down the glowing horizon of this new Fainting Dreams album, like the corona of the sun, a solar skin containing boundless light and beauty within it. The band established itself as a haunting slowcore/shoegaze peddler, one that caught our attention quite a bit last year. I delved into it a bit when we premiered “House of the Sacred Sisterhood” a while ago, something I felt honored to do, suffice it to say You Can Be Anything is a wholly different form of Fainting Dreams and for good reason. Assisted greatly by Madeline Johnston (Midwife) as a featured performer and engineer/mixer of this album, it has core member Elle Reynolds’ reckoning with her own reality from childhood to now and, effectively, what ‘you can be anything’ means to her.

Channeling the likes of Lingua Ignota, Ethel Cain, and more, Reynolds processes the unbounded spirit of curious youth and how it clashes violently with the confines of rigid expectation, causing an inner turmoil that’s capable of claiming lives. In other words, it’s a highly personal, sundering sermon on growing up transgender while entrenched in a hostile religious upbringing. ‘The album is narrative based, with the main theme being trauma, and the different ways it manifests overtime when left unchecked,’ Reynolds says. ‘Taking place in reverse chronological order, You Can Be Anything documents my past experiences as a trans person with self hatred and substance abuse as it works its way backwards to the religious violence and trauma I experienced growing up in North Carolina. It’s bookended by the two most extreme incidents of violence on the album, one being self-inflicted and the other being at the hands of others when I was a child.‘

Despite being a profoundly spacious and serene sound the album employs on every song with little variance, the weight is still immensely felt. Maybe it’s Reynolds’ haunting vocals, the slightly unsettling atmosphere, knowing what the themes of the album are, or just a combination of all of those things that presses down on your chest as you listen. This totality is certainly what further contextualizes “House of the Sacred Sisterhood” as the beginning of this story, the piano and associated vocal harmony representing the playfulness and innocence of being a child while the lyrics tell of the loss of it (‘I felt god when you struck me down‘), a turning point that informs every other song before it in the track list. The song’s more tainted with the feeling of loss and isolation after the midway point, a swirling of emotion building up as represented by the harsh screams seated far back in the song’s mix to represent this clawing discomfort, confusion, and repressed self wanting to break out the cracks.

Though not explicitly worded, the song is violent in nature, mentioning an assault as quoted above, but also trepanation, exorcism, and cleansing, all historical forms of ‘correcting’ someone as they are. This carries over in more explicit and implicit forms from song to song with Reynolds channeling the pain of being othered throughout her life from peers, her community, lovers, and even herself to a degree. Religious trauma smacks the hardest and has too many relevant threads to what LGBTQ+ people still deal with today in America and beyond. Every single account, bot or not, that I see on Twitter speaking disparagingly of trans people generally or directly has ‘Christian’ and/or a cross emoji in their bios, succumbed to hate and now making it everyone else’s problem. These days, Christ’s crucifix may as well be a dagger with which they stab their neighbors in the back as they run away in fear.

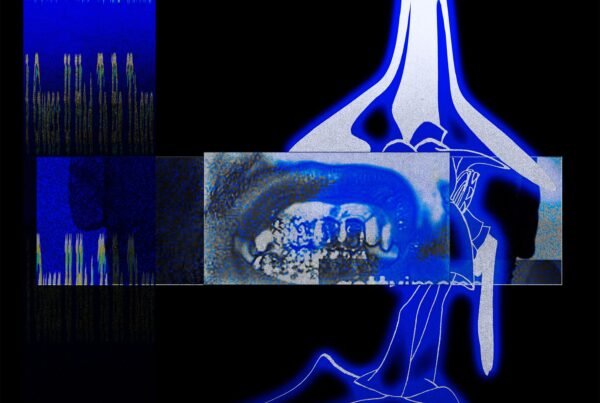

“Broken Walls and Covered Cracks” brutally details the efforts and lengths these people will go to punish and degrade anyone they can’t ‘fix’ as well as the toll it takes on the person simply living their life. Masking identity and hiding oneself isn’t enough to stop the dehumanization from people who don’t even know their names. It’s You Can Be Anything‘s saddest, yet most direct song, supported vocally by Midwife and Allison Lorenzen, touchingly bolstered by a sparse, somber piano line that complements the mood. Over a peaceful, numbing synthesizer, the title track is one of the most salient moments on the album with Reynolds recounting a point in her childhood, perhaps the first realization that she was trans, creating the crux of not only her whole life since, but for You Can Be Anything. The words, spoken in a hushed tone as if talking with someone while hidden in an attic, make up the text centered in the cover art as well, but they deserved to be read unobstructed:

‘I remember the first time I was really aware of anyone else’s body. I was 6 years old and I fell over at the playground and I cut my knee because I couldn’t stop looking at her skin, how soft it was. When I told my teachers I couldn’t wait to look like that one day, they told me it wouldn’t happen of course, because boys don’t grow up to look like that. That night when I was supposed to be asleep, I sat in front of the mirror, tugging at the cut on my knee and watching it bleed, and I kept having this thought that if humans are supposed to have 7 whole layers of skin, then I just needed to pull hard enough, dig deep enough, and maybe I’d find the parts of my body that actually belonged to me.’

Both parts of “Disappearing Act” jump ahead from there, where Reynolds reckons with the interpersonal complications with her identity and how they still inform the self and the mentality you carry into each day. Part I washes over you with synths that moan and twinkle with melody, as her vocals get a little more ethereal singing about being someone’s secret which is in of itself softly devastating (‘I’ll let you hide me away/In an old motel room/I’ll be the lover in your closet/I won’t tell anyone about it‘). The desperation for love and acceptance is palpable when she sings ‘If someone just loves me/Just touches me then it might cure this disease‘. Part II contends with the lies we tell others and ourselves about us, and trying to find the moral in the pain and suffering we’re subjected to. This too has allusions to religious trauma, being told that everything is in God’s timing and plan, and happens for a reason. It’s another moment of deep isolation as Reynolds can’t seem to find comfort in the company of others, wishing to be alone with the door locked and referring to her feet feeling bound and sinking down in metaphorical depths.

“Until I See Bone” – the first track on You Can Be Anything, but the final chronological stop in the story – is Reynolds’ attempt to baptize herself of the past via alcohol (‘Go fetch the holy water/No less than 45 percent‘). The imagery is the most pointed, yet harrowing here with the best line being ‘Take this bible belt and wrap it ’round my neck‘, a pitch dark apex of where the trauma, abuse, and repression leads a lot of people who can no longer fight a war to be themselves. The tones on this track sting of finality, a resolution in yourself as you hear fabled angelic choirs and drift toward the light. While it’s easy to read it as a suicide attempt (which may very well be the inspiration for the track), it’s more charitably – and perhaps more realistically – interpreted as a killing of the shame and pain that haunted young Reynolds as she found the parts within that reflected her truest self, picking at her skin until she saw bone. Just like on “House of the Sacred Sisterhood”, the final words are the most telling: ‘cleanse me‘.

Just like Melpomene did earlier this year in a much more extravagant and flashy fashion with no singing on A Body Is A Suggestion, Backxwash did with profound lyrical density on Only Dust Remains, and Hypomanic Daydream did weirdly (but no less accurately) with The Yearning, Fainting Dreams centers a search for self in the music. You Can Do Anything places tragedy and tears on one side of a scale where perseverance and bliss rest on the other side, searching for the perfect moment when the former begets the latter in a perfect balance. Though I’m not one to postulate that hardship is necessary for growth and the merit of being taken seriously or valued, this album has Elle Reynolds testifying to the grim reality many have faced and will face as long as we let people who deal in baseless, hypocritical hate get away with it, but it also shows what she values and holds onto from the very religion that placed its foot on her head and sought to stamp her out.

This album was recorded in Midwife‘s church space in Trinidad, CO, which undoubtedly is responsible for much of the atmosphere in each track, but it’s also a statement of personal power. Here Reynolds was, in a repurposed place of worship, singing just as she enjoyed doing in choir so many years ago before being exiled for who she was, in what I hope are times where she is more personally valued and respected by those close to her, where sanctuary is now a friend’s arms to make up for the times she wasn’t afforded that decency. It’s her telling others like her that you can be anything you want to be. This time it’s said without the veneer of exaggeration and white lies to save someone’s innocence, it’s said as a call for them save themselves while they are still able to.