Hello and welcome to another installation of EINthologies! This is a feature where a writer will choose a band of personal and general significance and go full nerd on them, as well as providing a guide to the band’s discography – I’m Hanna and I’m here to introduce you to one of my all-time favourite metal bands, and certainly my favourite death metal band, Carcass.

For a really quick introduction to Carcass, I will summarise – in 1980s England, guitarist Bill Steer and drummer Ken Owen formed the band when they were at school together, but never did anything with it, and soon after broke up. That’s it, the end! No more Carcass. Except…

Steer went on to join Disattack, a D-beat band, with a bunch of local blokes, and they released a demo in 1986, after which the bassist left and was promptly replaced by this guy called Jeff Walker, who used to be the guitarist and vocalist for the thrashy Electro Hippies. This pivotal lineup change, along with Steer also joining the now-legendary grindcore band Napalm Death around the same time, saw Disattack change style, name, and drummer – re-enter Ken Owen and the name Carcass.

So now we have Carcass almost as we know it, except that Disattack’s original vocalist Sanjiv was still part of it. After 1987’s aptly named Flesh Ripping Sonic Torment demo, Sanjiv left the band, and Walker, Steer, and Owen shared the vocal duties between them up until and including their 1988 debut album, Reek of Putrefaction.

It’s now been almost 35 years since Carcass released that first album back in 1988. While I’m too young and too far from Europe to have ever had a chance to see the band live, I do vividly remember my first experience with them. I was freshly into metal and I’d joined a band myself – the two guitarists took it upon themselves to ‘educate’ me, and gave me huge amounts of metal, which I diligently put on my iPod and listened to. I remember the day I first heard Carcass – it was a beautiful, sunny morning in 2014, I was on my way to school (funnily enough, my walk led me through the local cemetery), and I thought I’d give Surgical Steel a go. What drew me to this particular album, I don’t know, but I remember enjoying the opening instrumental, and being absolutely hooked by the end of the second song.

Surgical Steel was one of those ‘love at first listen’ albums for me, and remains one of my favourite records. Unbeknownst to me, it had been released only a year prior, but I didn’t realise it was recent at the time – I think I assumed it was ’90s death metal. It sounds traditional, in the best way, but simultaneously crisp and fresh. At the time I hadn’t heard much old-school death metal; I might’ve known about Death, but I certainly wasn’t familiar with them, so it was all new to me. Surgical Steel quickly became one of my most listened-to albums throughout high school. I did check out Heartwork and Swansong, but neither made much of an impact on me.

Somehow, Carcass slipped off my radar after I left school, until I was driving a long distance years later and needed something to keep me alert, so I chucked it on ‘for a laugh’ (or so I thought – I was going through a pretty snobby prog phase at the time). It was perfect, and reminded me why I loved this album so much. To this day, it remains my absolute favourite driving album (not always to the delight of my passengers). And yet Carcass fell off my radar yet again, until my bandmate mentioned something about them a year or so ago. Since then, I’ve been solidly delighted with them. They’re like that friend you won’t see or talk to for months, and then when you finally contact them again, everything’s the same as it always has been, as if no time has passed.

Over the course of their career, Carcass have released five EPs and six full-length albums, with their seventh being due for release in mid-September. Over the course of this EINthology, I will discuss all of their studio releases, with the exception of The Peel Sessions EP, Tools of the Trade EP, and The Heartwork EP, the former two because they feature almost exclusively songs that are also on one of the full-length releases, and the latter because it contains only two unreleased songs.

It was always hard for me to believe Carcass had started out as a goregrind band, considering my introduction to them was so melodic. I still feel that the band that had released Reek of Putrefaction was only vaguely related to the one that did everything afterwards. There are very few ‘Carcassisms’ on this early album; no trading guitar solos, no harmonised riffs or lead lines, not even vocalist Jeff Walker’s characteristic snarl – only the trademark lyrics about death and butchery were already present (though only infrequently decipherable).

Main lyricist Walker explains in a 1992 interview for Headbangers Ball that, around the time they started, Carcass were hearing all these death metal lyrics that were misogynistic and homophobic that they weren’t so into. When drummer Ken Owen began writing some very extreme, gory, medical-themed lyrics, the band were instantly on board. In the 2007 Carcass documentary The Pathologist’s Report, Walker remembers: ‘when I saw the lyrics, I saw how funny it was, how stupid and how ludicrous and how extreme we could take it, so I really got into it, I was sold on it’.

Reek of Putrefaction has 22 tracks on it and comes in at just under 40 minutes – the songs range from a snappy 22 seconds to a little over 3 minutes, and all the song names are, frankly, ridiculous. Some of my personal favourites include “Vomited Anal Tract”, “Excreted Alive”, “Pungent Excruciation”, “Manifestation of Verrucose Urethra”, and “Oxidised Razor Masticator”. The band’s love of the obscene and gruesome has always been a part of their aesthetic, and would continue to be for the vast majority of their career.

The one phrase I can think of to accurately describe the entirety of this album is ‘rough as guts’. Both sonically and musically, Reek sounds primitive, underdeveloped – it’s a tricky listen, not least because the production is inconsistent at best. The drums struggle to be heard above the murk of muddy guitars and ferocious but untamed vocals at some points, and at others cut through with so much bite it’s borderline painful. Similarly, I feel the riffs themselves are struggling to decide whether they want to be a blur of chromaticism or defined bursts of brutality, and the vocals fluctuate between Steer’s almost literal barking and Walker spitting out clearly enunciated phrases. Even after many listens, I still think the album is largely confusing, overwhelming, and feral.

Just how I feel a little alienated by Reek, Carcass themselves struggled to come to grips with it for some time, too. The band felt that the engineer ‘made a complete dog’s dinner of it’, and Walker, in a 1992 interview for Headbangers Ball, admits that ‘for a period of time, we disowned Reek of Putrefaction because…we thought it was just too nasty basically’. In the 2007 Carcass documentary, The Pathologist’s Report, he elaborates: ‘it was totally heart-breaking at the time, disappointing, it could’ve sounded better…having said that, in retrospect, I fucking love it now, ‘cause it’s just so horrible sounding’. Guitarist Steer has also come to see it as ‘a weird artifact from that era…it’s such a bizarre recording, and it sort of represents where we were at, ‘cause we weren’t great musicians, we were very inexperienced’.

Reek is one of those albums that, even if I struggle to truly enjoy it, I can appreciate as exactly that: a timestamp, a snapshot of the Carcass that was playing small, local death metal shows in the late ’80s. I wonder as well though whether Reek of Putrefaction would be the grindcore classic it is seen as today, had the band gotten what they wanted from the production in the first place. Perhaps its choppy riffs and edgy vocals would sound out of place graced with better drum production and clearer tones, and perhaps it’s exactly this challenging production that set it apart from the relative pristinity of its contemporaries, such as Slayer’s South of Heaven, Manowar’s Kings of Metal, and Iron Maiden’s Seventh Son of a Seventh Son, and kept it in the same realm as Death’s Leprosy (which also suffers from, well, lacking production and underdeveloped songwriting).

Both Reek of Putrefaction and 1989’s Symphonies of Sickness famously featured album covers that, rather than depicting a scene of fantasy violence, were simply collage of dead things – the former features autopsy images, the latter a combination of human and animal corpses. I find them both equally unappetizing; meat everywhere, utterly unappealing. It can be hard to tell what kind of limb one is looking at, and what kind of animal it might’ve come from. It’s gross and confronting, and that’s precisely the point – in Sam Dunn’s excellent metal documentary series, Metal Evolution, Walker talks about intentionally ‘making an analogy of ‘dead corpse, dead corpse‘ – human or animal, what’s the big deal?‘.

In Metal Evolution, Carcass also talk about never being into the ‘cartoonish elements of metal‘ and wanting to be more real. At the time of making these albums, they specifically chose not to have the covers depict fantasy horror like so many metal bands at the time were doing, as there’s already so much gore in real life. The entire ‘original’ lineup of Walker, Steer, and Owen are vegetarians – having been a herbivore myself since I had the ability to understand where meat comes from, this just makes them infinitely more badass in my mind. Steer reiterates: ‘we weren’t aggressive people‘, but both him and Walker agree their intent was absolutely to ‘disturb people‘.

I should also add here that the 1987 Flesh Ripping Sonic Torment demo features a lot of the same songs as Reek of Putrefaction, but feels, to me, like a much more honest representation of what this album should’ve been – raw, but in the right way. I prefer it, so maybe if Reek alienates you, this will be a better alternative for you, too. Check it out, it’s pretty vicious (plus, it’s the only Carcass recording to feature original vocalist Sanjiv, so that’s an interesting difference, too).

I had never really listened to Symphonies of Sickness before I decided to tackle this article, and, after the relative shock of Reek, I was pleasantly surprised by it. It’s got a whole heap of Carcassisms in there – Walker himself feels that it’s their ‘first album, in a way’, and I can only agree. It’s got the aggression and occasionally goofy harsh vocals of Reek, but it’s also a huge step forward in sophistication, not just musically, but also in terms of its overall sound. Walker explains that the band were redefining themselves on Symphonies, and sees it as the album on which ‘we formed our own niche, we created our own style’.

On Symphonies, Carcass started what would become a long-lasting partnership with engineer Colin Richardson. Not only was Richardson much more particular about the sonic qualities of the band’s sound, he also brought some new ideas to the table and gently coached the band in terms of their playing. Steer says that ‘when we met Colin Richardson, it was a godsend, because he was so open-minded’. Richardson would work with Carcass on all future releases, and have a huge impact on their sound and direction.

As well as being a big step forward in terms of production, Symphonies of Sickness is also a lot more deliberate in how the songs are composed. One of my favourite tracks is “Excoriating Abdominal Emanation”, a gruesome blend of blast-beat-fuelled, tremolo-driven death metal and mid-tempo chugging, with the vocals almost entirely double-tracked high and low. On this track, Carcass do something that’s missing from Reek of Putrefaction – they include a riff that relies more on what notes aren’t being played than the ones that are. This creates a slightly eerie split-second of deathly silence, catching the listener off guard after almost two minutes of furious onslaughts.

In fact, a lot of songs on Symphonies play with silence and how much of an impact it can have. You can hear the trio testing the limits of contrast, and most songs on the album strike some sort of balance between brutality and groove. There are moments that are pure grindcore chaos, and yet there are sections that seem almost beautiful, too. The whole album still sounds raw, but in a much more intentional way than its precursor.

“Exhume To Consume” is a great example of this – it still has the thrashy, raw power of grind, but isn’t afraid to weave in the odd melody (harmonised, even!), or succumb to a bit more groove. There are even little pieces of ear candy in the chorus, a guitar screaming like a knife being sharpened. Carcass manage to jam a lot of different and contrasting ideas into this one song, but because of its reasonably straightforward structure, it doesn’t feel alienating at all – it just works. On Symphonies, it becomes clear that the band understood the impact of sheer, ear-splitting brutality, but also that it’s so much more effective when placed next to something groovy, slower, or more melodic.

Already in 1990, only a year after the release of Symphonies, Carcass knew they would be going even more melodic. In an interview for Peardrop, when Steer was asked whether he thought they were ‘more melodic than Morbid Angel’, he mentions that while there was no way to compare these two bands, there would definitely be more melody on their next release – but he also assures the interviewer that ‘the sound will always be grotesque, and the melodies we use are unusual ones, not just ‘nice tunes‘’.

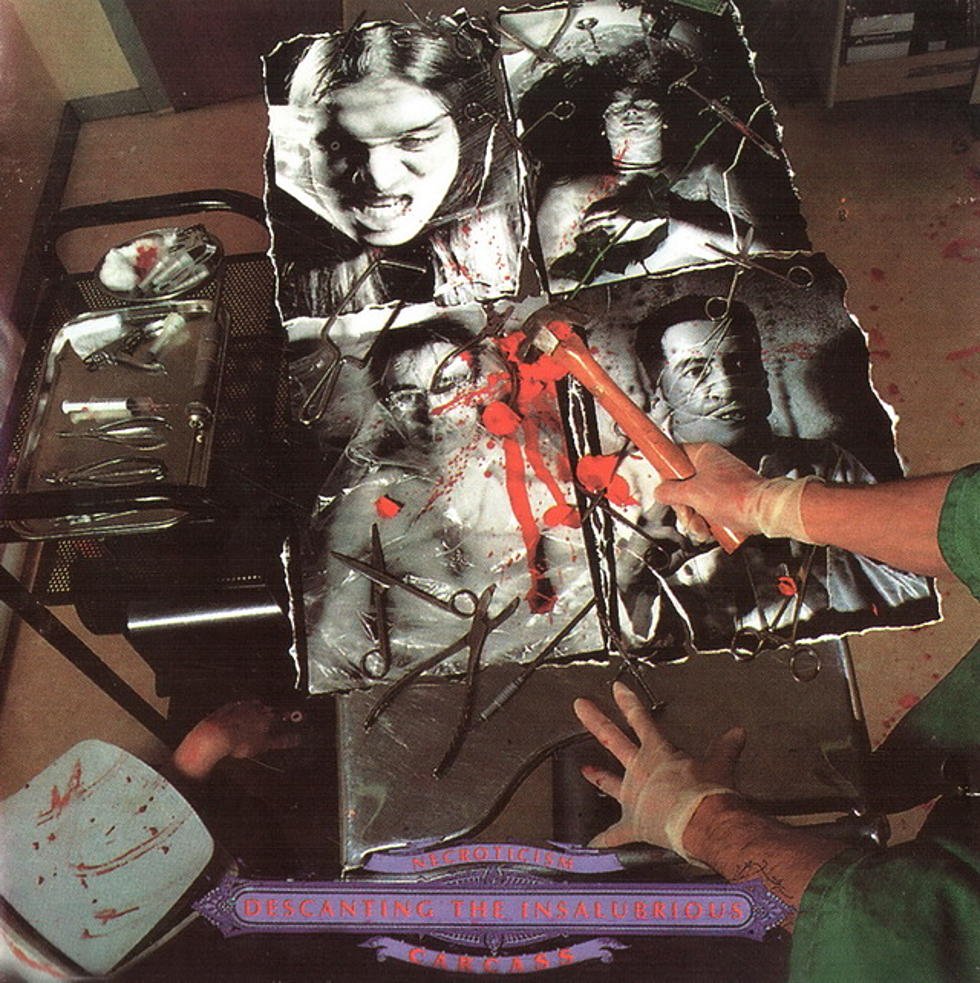

Well, let me tell you, our mate Steer wasn’t lying. 1991’s Necroticism – Descanting the Insalubrious is, from its very beginning, just as morbid and gross as we’ve come to expect from Carcass by now, opening with a snippet of a woman talking about autopsy procedures for bodies that are so disfigured that the cause of death can’t be easily identified. While the music does reflect this unsavoury subject matter in the same way Reek and Symphonies did, with evil riffs and the classic ‘grotesque’ sound, Necroticism is…different.

Right from the opening track “Inpropagation”, it’s clear that this is a new version of Carcass. They sound focussed, self-assured, lean, and mean. While the songs and the album itself are longer, there are only eight tracks on Necroticism, stripping back further from Reek’s 22 and Symphonies’ 10. The album is in a completely different league from the scattered Reek, and makes Symphonies sound like exactly what it is – a bridging album. The arrangements of the songs on Necroticism are so much more sophisticated than anything before, helping keep the songs interesting despite their increased length. Steer comments on this seemingly rapid change in direction:

‘When you’re younger, you’ll go through things really quickly, so you’ll have a phase on something, and it feels like it’s really intense and lasts a long time, but it’s really just six months or a year. You can see that with Carcass a bit, with the third record we got into very complex music…for some reason, we thought that all of our songs had to be very complicated’.

Walker in 1992 described the album as ‘a leap again’, saying that they’d gotten all the ‘extreme stuff’ out of their systems. And while it is true that Necroticism may not be as ‘extreme’ any more in terms of speed and harmony, it is still very much the band pushing themselves and the boundaries of metal at the time. Looking back on it in 2014, Steer explains:

‘There were loads of bands, or at least, enough to make us nervous, that were doing something similar to what we’d done on the first two records…so I think we just wanted to push it harder, in a more difficult direction, to prove to ourselves as much as anybody that we could do it’.

This sentiment was seemingly shared by a lot of death metal bands in 1991 – all over the place, bands were pushing what death metal could sound like, be it in a more gruesome, technical, progressive, or melodic direction. Along with Cannibal Corpse’s (in)famous Butchered at Birth, Pestilence’s Testimony of the Ancients, and Gorguts’s debut Considered Dead, it was also the year that Death released Human, possibly one of the most influential death metal albums ever. There seemed to be a restlessness, an urge not to become irrelevant copycats of each other, a struggle to gain autonomy in a scene that was snowballing in popularity and about to splinter off into innumerable subgenres – and it worked out very much in favour of the bands that took risks.

While Necroticism may not have had as obvious an impact on the death metal scene of the ’90s as Human did, it still signifies a very important shift for Carcass themselves – a huge step away from almost anything grind related. While there are still some vicious riffs on this album, they are much more measured and refined, and take less of a central role within the album overall. Necroticism is filled with riffs, but also melodies, and a selection of tasteful-yet-technical solos – where there were moments of Kerry King-style whammy action on Symphonies of Sickness, there are now clean-cut, well-executed phrases. Necroticism is a good introduction to Carcass if you find yourself drawn to slightly rawer, heavier music.

If there’s one thing this album isn’t, it’s lazy. Nothing is forced – none of the transitions between riffs sound rushed, or overcomplicated. The surgical precision Carcass would become known for becomes slowly evident throughout Necroticism; it feels like everything is where it needs to be, not to mention the musicianship on this album far exceeds anything prior. With the addition of guitarist Michael Amott, the band really started to explore the opportunities a second guitarist could open up, particularly in terms of leads and solos. While Amott did contribute some leads and solos on Necroticism, his influence would have much further reach on Carcass’s spectacular next album: 1993’s Heartwork.

As Carcass-y as Symphonies of Sickness and Necroticism are, for many people, the pinnacle of Carcass and the most recognisable version of their sound was born with their 1993 album Heartwork. While the album was just as groundbreaking and, in many ways, unexpected as its predecessors, it also heralded an era of more consistent progression – from here on out, they became a melodic death metal band. That’s not to say they’d lost any attitude, but the rough grit of the three previous albums took a back seat – Heartwork takes the cleaner production, more concisely structured songs, and overall more focussed sound of Necroticism and takes it about five steps further. If you’re new to Carcass and not already into death metal, this is a great album to start with.

On Heartwork, more emphasis is placed on clarifying harmony and melody, where previously the band may have favoured musical aggression over melodic content. Already on the opening track, “Buried Dreams”, we are given spectacularly harmonised lead lines and two exquisitely phrased guitar solos, including one with wah used so tastefully it could give Kirk Hammett in his prime a run for his money (courtesy of Amott). But fear not, this doesn’t mean there’s no more anger on Heartwork – Walker’s snarl is still blisteringly hair-raising, and there’s no shortage of furious riffing.

In fact, up until Heartwork, Walker and Steer had largely shared lead vocal duties, with drummer Owen occasionally contributing backing vocals, but Steer was not prepared to do the same on this new album. The absence of his vocals robs the album of a little bit of contrast – I always enjoyed the interplay between Walker’s snarl and his growl. Walker agrees: ‘if I’m honest, I think the album suffered from not having his [Steer’s] vocals on it – all you got were mine, and I don’t believe that was enough’.

Despite this small drawback, many of the tracks on Heartwork are fantastic examples of everything Carcass were ever about, especially “This Mortal Coil” – it features a straight-out-the-gate breakneck riff, lovely harmonised guitar playing, a smack of groove, catchy choruses, and a tasteful yet shreddy trading solo section. In fact, all three tracks at the start of the album’s second half are absolute slappers: the previously mentioned “This Mortal Coil”, the clean-cut and groovy “Arbeit Macht Fleisch”, and my personal highlight, “Blind Bleeding the Blind”.

This track stands out above the others to me thanks to its slightly more technical and explosive nature, as well as its bookends of trading licks between Steer and Amott, each slipperier and bluesier than the last. The song shifts surprisingly but seamlessly between its fast, ascending opening/main riff, some odd, shifting progressive licks, and chunky, meaty mid-tempos. Where the song’s opening trading licks were bluesy and pentatonic, the ones near the end are pure metal shred.

To be honest, much as I enjoy Heartwork, it doesn’t inspire the same degree of near-obsession that I get with Surgical Steel. I’m not really sure what that’s about – the two albums are stylistically and sonically quite similar, and Heartwork doesn’t have any faults I could put my finger on. Something about it doesn’t seem as forceful, perhaps; maybe there was a bit of fatigue creeping in, being the fourth album Carcass had released in just over five years. The band had changed sound dramatically from the gory, grindy beginnings of Reek of Putrefaction, and had been playing live almost constantly.

On top of this, the recently indoctrinated Amott was showing signs of losing interest – in the band’s documentary, Walker says that despite writing a lot of material for the album, when it came to the recording, Amott ‘basically came in just to play his lead’. Amott had recently started a more classic rock-influenced band called Spiritual Beggars, and had mentioned that he planned to leave Carcass after the Heartwork tour to the band’s manager. After Walker and Steer found out about this, they decided to ask Amott to leave before the tour ‘rather than dragging it all out’. Enter Mike Hickey, a roadie who ‘brought a real injection of energy and enthusiasm’ to Carcass’ live shows.

Prior to the album release, the quartet had already played all the tracks from the new album live, and they were largely well-received. The album also charted at number 54 in the UK, the first Carcass release ever to break the top 100 – but somehow, the fans proved to be hard to please. In a 2007 interview with Metal Hammer, Walker explains ‘when it came out, all we got was indifference, and a lot of accusations that Carcass had ‘sold out’’. Steer, in the 2007 documentary, says the same thing:

‘The album got quite a frosty reception, especially in the States. I remember meeting kids and they’d be saying, ‘You sold out.’ [At our concerts] people would say, ‘It’s good to see you lot playing‘ et cetera, et cetera. And as they were drifting away, they’d say, ‘Actually, I think the record sucks’. I didn’t meet anybody who liked it. It almost felt like we’d messed up in terms of delivery of what our audience wanted to hear.’

We have now reached easily the most divisive album in Carcass’ discography – the ominously named Swansong. Following the commercial success of Heartwork (regardless of the fans’ reception of it) and a freshly-forged deal between Earache Records and Columbia, the album was designed to be the band’s big debut on a major label. However, the deal didn’t sit right with the band – Walker remembers ‘it was obvious [Columbia] didn’t give a shit. At times, we felt like we’d been thrown into a Spinal Tap scenario, meeting all of these executives who didn’t know who we were – and didn’t care’. On top of this, the band actually broke up before Swansong’s release in 1996, which, along with the record’s name and all it implied, possibly only fuelled fans’ disappointment at the album.

So, what makes Swansong so controversial? On the face of it, it seems like a reasonably natural progression for the band – the album is much, much poppier, with lean, catchy songs, straightforward structures, and overall much more rock ’n’ roll leanings, but it still sounds undeniably like Carcass. Somehow, though, it also sounds like the band taking the piss out of themselves. It’s almost like they’re trying to simplify, to become more accessible, and even the convoluted song names and gory subject matter are absent – the closest would be “Keep on Rotting in the Free World”.

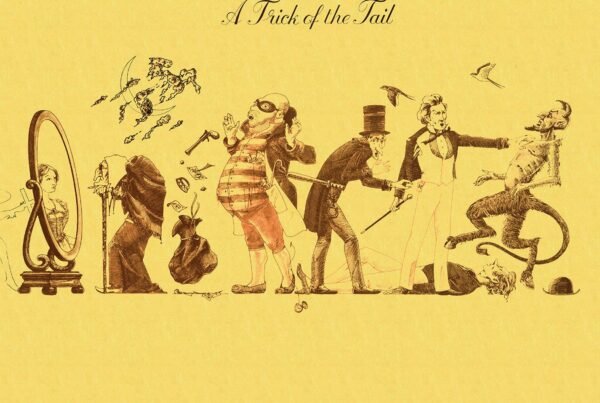

Something about Swansong tickles me: I still don’t know how I feel about it. It’s an album I managed to pick up on CD not too long ago, and, just like its younger sibling Surgical Steel, it lends itself to driving – I’ve become quite familiar with it. I do love this album, but whenever I say or think that, I do it hesitantly. Something about Swansong feels tongue-in-cheek, passive-aggressive. I think I feel like Carcass are tricking me, like they’re having a chuckle at how Swansong baffles me, and all the rest of their fans.

Looking at 1996 in music, I can kind of see why fans were disappointed – grunge was the big thing, but death metal had a few stand-out releases nonetheless: Cannibal Corpse’s Vile, Dying Fetus’s Purification Through Violence, and Cryptopsy’s None So Vile. All things considered, though, the extreme metal scene was looking a little worse for wear, so it’s understandable that when the fathers of goregrind, inventors of melodic death metal, Lords of Snarling Vocals and Blazing Guitar Harmonies Carcass came prancing in with the catchy, tongue-in-cheek Swansong, people just didn’t get it. In the words of Jeff Walker himself: ‘I gather that [Swansong] was pretty much roundly despised’.

In a 2014 interview, Steer sheds some light on the circumstances surrounding the album and its release. Interestingly, the title ‘Swansong’ was only chosen quite far into the release process; originally, Carcass had about 15 songs written, but no name for the album. They weren’t even sure which tracks were going to make the cut. Steer was about ready to quit around this time as well, and explains that ‘we were just sick of each other as people, and musically maybe a little too’. He remembers saying he was quitting a few times, and when asked why, simply responds: ‘I was fairly certain there was no future for us, really. When we were rehearsing the material, you could tell it was over, I thought’.

Then, one day in 1996, it was over – Carcass had split up. Steer, disappointed with how the band ended and that they hadn’t managed to release the ‘one more good album’ he felt they should’ve had in them, didn’t even listen to Swansong for a long time after it came out. He elaborates:

‘I just really wanted to close that chapter. I was so bitter when Carcass broke up. I’m sure the other guys were, a little, as well, but not to the same degree as me. I just didn’t want to hear anything about it, or anything from that scene – I really just wanted to escape it’.

Slowly, though, Steer came around, and he recognises now that he was ‘just young and taking everything too seriously, and I had to take everything to an extreme’. Until 2007, it seemed like Swansong really was living up to its name – the final, dying effort of a bitter, disillusioned band from the ’80s, who couldn’t relate to where metal was heading, and who had, essentially, burned out. It took both Walker and the long-independent Amott mentioning to Steer that the band still had a following for him to gradually come to terms with a reunion; he admits ‘I was very cynical at first, but gradually, I guess they persuaded me that there was enough interest for us to play again’.

I’m going to try keeping this section short. I’ve already talked quite a bit about my personal relationship and experience with this monumental release, and I’m sure there’s only so much worship of one album you can take. So let’s stick to the facts and the story behind it.

Carcass reformed in 2007 and went on a reunion tour of sorts, accompanied again by guitarist Amott. Unfortunately, drummer Owen had suffered a cerebral haemorrhage in 1999 that left him unable to play, so Carcass were joined by Amott’s Arch Enemy bandmate Daniel Erlandsson, however both him and Amott left the band after the reunion tour to redirect their energy to Arch Enemy. Steer and Walker, not content with merely being a reunion band, recruited drummer Dan Wilding after Steer found himself inspired by Wilding’s similarity to Owen; and quietly, Carcass started writing again.

The new (old) Carcass had no trouble getting straight back into their groove – Steer states ‘it was very easy to get into this because nobody knew we were writing. This was just between Jeff [Walker], myself, and Dan [Wilding]…but it felt very good really quickly’. It took only a year from Wilding joining the lineup in 2012 for them to release the single “Captive Bolt Pistol”, and, finally, in September 2013, Surgical Steel hit the record stores (and internet).

Even though Surgical Steel is the definition of a comeback album, released after a hiatus of nearly two decades by a band that was reasonably well-known in the late ’80s and ’90s, it doesn’t sound like that at all. Even the term ‘comeback’ is misleading – it brings up notions of washed-out has-beens trying to grab hold of the last shreds of fame they may have, and forcing out a flaccid release just to ensure their retirement fund stays topped up. Surgical Steel is not the final, desperate attempt of an aged band trying to become relevant again – it’s pure, beautiful, melodic death metal goodness, without pretentiousness, and without fatigue.

The album is jam-packed full of riffs – kicking off with the violent “Thrasher’s Abattoir”, which is just under two minutes of tight rhythms and vocal bursts, and all the way to the epic eight-minute album closer “Mount of Execution”, there’s never a dull moment. I could easily and happily write about every song on the album and why I love it, but I’m sure you’d rather discover it for yourself. I will point out the absolutely fantastic guitar solos that form the climax of “Cadaver Pouch Conveyor System”, a classic guitar duel between Steer and, uh, himself. On this album, Carcass didn’t have a second guitarist, but Steer does a damn fine job of portraying two completely different sides of his playing in this section – for a long time, I thought it was two different guitarists playing.

However, to me Steer’s most memorable Surgical Steel solo is on “A Congealed Clot of Blood”, which has been one of my absolute favourite Carcass tracks since I first heard them. This particular solo starts off low, slow, and slippery, winding and weaving, almost classical in its lyricism, and slowly becomes busier until Steer can’t contain himself anymore and throws in some absolutely pristine shredding, before letting it peter out to make way for one final riff. He brings this sensitivity and tasteful sense of phrase to every solo after Symphonies of Sickness, but I find he shines the most on this album – it’s like all these years of not playing metal have left him with a wealth of pent-up melodies, and he’s just spitting out gems all over the place.

On top of having some of Carcass’ best solos, tightest riffs, and the snarliest Walker snarl paired with the beefiest Steer growls, Surgical Steel also sounds amazing. There’s a richness to the production that was still a little lacking on Heartwork, with the main rhythm guitar tracks often consisting of four layers and being subtly fattened by sustained chords hiding behind the bass. It sounds like the 17 Carcass-less years between Swansong and Surgical Steel had left not just the band but also long-time producer Colin Richardson with more to give than they ever had before.

Despite my ridiculous love for Surgical Steel, I veered away from its EP counterpart Surgical Remission/Surplus Steel right up until I was writing this article. I think I was afraid to tarnish my near-religious worship of Surgical Steel by making myself listen to what I thought would be ‘just some sub-par B-sides’ that didn’t make the cut, so I looked the other way whenever I came across SR/SS. What a foolish thing to do.

There is nothing ‘sub-par’ about this EP, and the songs certainly don’t feel like B-sides. Any of the first three tracks could’ve and would’ve fit in seamlessly with the rest of Surgical Steel, from the unbridled ferocity of “A Wraith in the Apparatus”, to the chunky grooves-gone-evil of “Intensive Battery Brooding”, and finally, the grim riffing of “Zochrot”. The one song that breaks the mould and would’ve undoubtedly felt awkward on Surgical Steel is “Livestock Marketplace”, not just because of its slightly more conservative writing style, but primarily because of the vocals. Walker isn’t snarling here – he’s doing more of a low-pitched Dave Mustaine impersonation (if you can imagine that), as well as actually giving most phrases…pitch! It’s very different, an outlier both on the EP and in the context of Carcass’ discography in general, but that doesn’t make it bad – it just takes a little more getting used to.

SS/SR is a fantastic continuation of the near-perfection Carcass achieved on Surgical Steel. Even though I normally recoil when I see a reprise of a song on any release, I felt “1985 (Reprise)” was a natural and appropriate end not just for the EP, but the ‘Steel’ saga overall. Listening to this EP for the first time took me right back to my early days with Surgical Steel – it made me screw up my face with giddy abandon, sent adrenaline through my veins, and reminded me, through its morbid lyrics and vicious energy, that it’s good to be alive. Don’t make the same mistake I did – do not skip this wee gem.

Even though Carcass opted to put off the release of the album they’d announced for mid-2020, they still gave us something utterly delightful – the slamming EP Despicable, which my fellow writer David and I had the absolute privilege of reviewing together. It’s only four songs, but each one is utterly memorable and awesome. Even though the EP lacks one of my favourite Carcassisms, the trading of solos between the guitarists, I couldn’t be too disappointed, as the solos that are on it are all supremely tasteful.

There are also just so many clever details in the production of it – subtle percussion moments, lovely floating lead lines, and an absolute crystal clarity. The EP screams not be overlooked, and it certainly shouldn’t be – it’s a force to be reckoned with. On Despicable, Carcass expand on what they started exploring on Heartwork and continued with Surgical Steel – finding the perfect blend between brutality and beauty. Sure, Despicable is a bit more laid back, far groovier than its 2014 predecessor, with more mid-tempo riffs and less shredding, but it’s just as cleverly constructed and finely executed.

Like everything Carcass have released since Heartwork, Despicable is exhilarating. If I’m having a bad day, all I need in the chorus of “Under the Scalpel Blade” or the sassy second half of “The Living Dead At The Manchester Morgue” to get me groovin’ again. Many a foul mood has been tamed by this baller of an EP, not to mention its older siblings. Even moments of Necroticism and Symphonies have this uplifting effect on me, despite being quite morbid and gruesome (lyrically at least).

At the time of this article’s publication, Torn Arteries will not have been released yet – I won’t give too much away, but David and I will again be writing a duo review, and all I can say is: I’m so keen to share my thoughts on this album. I find myself reminded again how much of a privilege it is to hear this before most other people (not to brag! I just really love Carcass!). The two singles released to date slap pretty hard, so hopefully you’re as excited about hearing the rest of the album as I am about getting to review it.

Torn Arteries will be released on September 17 via Nuclear Blast – you can now pre-order some pretty sweet vinyl variants as well as the CD here.

Well, there you go! That’s Carcass in a nutshell. Of course, there are so many subtleties of the records and the stories behind them that I just didn’t have time to squeeze into this feature. If you’re interested, I highly recommend you have a look at The Pathologist’s Report – I found it hugely enjoyable and informative, an excellent source of insight not just into the band’s history, but also their personalities – plus it’s as close to having a beer at the pub with Carcass as I’m ever going to get.

Writing this feature, I also learnt a lot about my own relationship with Carcass. Beyond becoming more and more enamoured with them the more I learnt about them (that British wit, I can’t get enough of it), I also realised that they are the only one of my favourite bands for whom my love is not based on emotional response. I just enjoy their music for what it is – sick, fat, riff-fuelled goodness. So, gents, thank you. Keep on rotting!