Oh, the ’80s – for whatever reason, I imagine this decade as an endless parade of hairspray. Don’t ask why. NASA launched the very first Space Shuttle mission, MS DOS made its debut on personal computers, Lady Di married Prince Charles and a long lost Mozart symphony was discovered. A wild year – also for music. Let’s discover some of the gems, shall we?

Ozzy Osbourne – Diary of A Madman

released October 1981, by Jet

revisited by Landon Turlock

The year is 1981. Ozzy Osbourne, who rose to fame as the vocalist of metal progenitors Black Sabbath, recently reinvigorated his career with his debut solo record Blizzard of Ozz only a year earlier. I imagine a lot of fans were enthusiastic about hearing a sophomore release so soon, and the result was Diary of A Madman.

I do not remember a time in my life where I was not listening to Black Sabbath and Ozzy Osbourne. I grew up the child of a father who was in a touring hard rock band in the ’80s, and I was raised on a lot of the music he played in bars across Western Canada. “Crazy Train” was one of the coolest songs I knew before I even knew what a riff was, what tapping was, or, frankly, who Ozzy Osbourne or Randy Rhoads were. As I became a musician myself, I always especially gravitated towards Rhoads’ incredibly melodic neoclassical style, and his influence has shaped much of my writing and taste since.

So you can probably imagine that I might have a lot of love for Diary of A Madman… but I think that would be an overstatement. It might be that I am now listening to the 42 year-old album with 2023 ears, and I try to account for that. 1981 was a time you could pose in B-movie horror make-up on an album cover, have cheesy horror synths all over a record, and write self-serious ballads about the immortality of rock music (looking at you, “You Can’t Kill Rock and Roll”). We’re in a different place culturally and musically, some of which is owed to albums like this one.

I think it is fair to say Diary of A Madman takes some of the eeriness of Blizzard of Ozz and explores it further – a trajectory that began with Black Sabbath and is a staple of Osbourne’s musical aesthetic.

But my main critique of the album is that it feels undercooked. There are some genuinely fantastic songs on the record. “Over the Mountain” is epic, fast-paced, and incorporates some genuinely inspired lead playing from Rhoads. In some ways, it feels like a song that set the stage for much of the thrash music that was developing close to that time. “Flying High Again” has so much swagger that it’s hard not to love. Those two songs opening the record makes for an incredibly successful introduction. However, almost all the rest of the songs are… ok. To me, most of them lack the charisma, memorable riffs, or guitar heroics that made me love Blizzard of Ozz.

That is, until we get to the closing title track. The song blew me away as a kid, and it still does as I approach my 29th birthday. “Diary of A Madman” is a masterpiece. Its nylon string intro builds perfectly into a haunting, dramatic, and instantly memorable riff. While I feel like I have to say that, especially as a person living with mental illness, I am sensitive to how we discuss mental illness in media, and I don’t believe that this song’s lyrics are particularly thoughtful in this respect. However, as a whole, the song builds from what was accomplished on Blizzard’s “Revelation (Mother Earth)” and takes it to a whole new and epic level. The song’s fantastic bridge builds with strings and choirs into a phenomenal solo and probably one of the coolest album outros I have heard to this day. In the 42 years since, I can definitely imagine how this track directly or indirectly influenced bands from Metallica to Coheed and Cambria to The Human Abstract, and maybe even Archspire or First Fragment.

Ultimately, I still think that Blizzard of Ozz is a more consistent and energetic record than Diary of A Madman. However, even despite its shortcomings, when Diary succeeds, it has some legendary moments that I think are influencing progressive and heavy music to this day. How many records can you say that about?

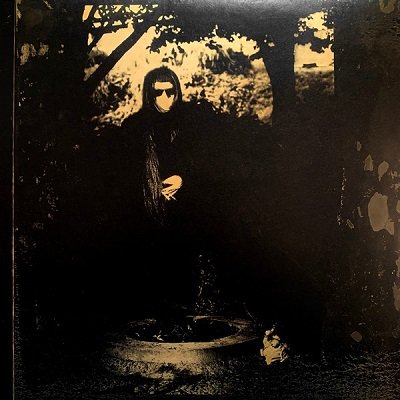

Keiji Haino – Watashi Dake?

released September 1981, by P.S.F. Records

revisited by Dom South

By 1981, Keiji Haino was far from a newcomer in the world of the Japanese avant-garde. He had already fronted the jazz ensemble Lost Aarraaff, formed his long-running power trio Fushitsusha, and become a fixture on the live circuit with his exciting, eccentric, and ethereal performances. Performance is a key term here, as the young, impressionable Haino’s first love was the theatre, spending much of his youth performing in plays, only later transitioning to music. The music that really caught his attention was the raw blues of the USA and psychedelic blues rock of The Doors. He loved the emotions, the power of the performance, and the sometimes chaotic pure sound. Watashi Dake? (translating to ‘Only Me?‘) encompasses a lot of his early loves, with this being his debut album it could be expected, but it was the start of one of the most incredible discographies we’ve ever seen.

Opener “Ore No Arika” (‘My Refuge’) begins with a shout and a period of quiet. There is an astounding amount of quiet, silence apart from the whir of the recording, with his now trademark shriek the most notable part of the song. It takes until the second offering to hear some conventional instrumentation. Here and for most of the album thereafter, it is a solo acoustic guitar paired with his otherworldly vocals. While the raw sound, simple guitar playing, and emotional vocals does somewhat recall the raw delta blues of Robert Johnson or Blind Lemon Jefferson (a particular favourite of Haino’s), it eschews the 12-bar format completely. This sounds as if an alien tried to describe the blues to other aliens. His voice whispers, shouts, shrieks, and squeals with tremendous emotion and a noticeable drama which surrounds much of his work. What really pervades across this album is just an essence and an aura of the performer himself. You can feel his emotions even if you can’t understand his words. The guitar playing is haphazard and doesn’t sound like the guitar should, yet it’s instilled with such character and creates an incredible atmosphere.

Throughout Watashi Dake?, there is somewhat a lack of depth with the lack of instrumentation, but he creates such noise and volume it doesn’t matter. Walls of feedback and noise have become a key part of much of his music, but the mix of loud and quiet is another noticeable feature. This album is recognisable as the birth of much of what we know of Haino’s music, yet not many of his albums sound massively similar in style. Some albums have followed the style, notably Black Blues (though this was released twice, as Soft and Violent versions), but he has created such a range of music since that it stands as a beginning that has rarely influenced his thinking. He has remained a musician at his best when running on impulse and following his mind no matter where it takes him musically.

Even without the proliferated chaos of much of Haino’s music, this is a tremendous album that has become a fan favourite and extremely hard to find. The myth of Haino is a good reason why, but in itself this is astounding and incredibly exciting. “Rowa ni saseru” (‘Lay It Open’) has a mix of clean and thrashed guitar parts; this thrashing is a technique that would become familiar in the following decades. “Umaku dekinai” (‘I Can’t Do It Properly’) starts much like the other songs on this album before exploding into loud distorted chaos, with Haino using his voice with more force to overcome the aggressive guitar he seems to be battling. “Kuzurete yuku” (‘Falling Apart’) manages to make the most of quiet, as the track eerily moves forward with high-pithced vocals quietly floating over a barely played guitar.

Watashi Dake? remains a notably pure album in Haino’s discography. This is a man who has incorporated the hurdy gurdy, electronic instruments, and the looping of his own voice into his music, creating layered soundscapes unlike any other musician has ever created. This debut album serves as an intriguing album in itself, even more so as you delve into the chaos of Haino’s career.

Kraftwerk – Computer World

released May 10 1981, by Kling Klang

revisited by Carlos Vélez-Cancel

For a genre that I’ve never dug too deep into, I’ve come to be particularly fond of electronic music. For this, I owe it all to Kraftwerk – such household name has consistently sparked in me both nostalgia and fascination throughout the years, and even to this day, with their seminal eighth full-length album Computer World, weaving that common thread with a force only a handful of records have been able to achieve.

One might not imagine discovering impactful (let alone great) music at questionable metal forum sites back in the heydays of the internet, but that was precisely the case with fourteen year-old me stumbling upon someone’s signature block of a yellow background with a computer terminal at the very center of it. That for some reason caught my attention immediately, and after clumsily browsing through the web for a good while (I don’t think reverse image search was a thing back then… Jesus), well, the rest was history.

Of course, I didn’t think too much of Computer World when I first listened to it, as I was too busy keeping my metal creds intact. And yet, something about it lingered in me since then. I began to occasionally revisit some of the tracks on there, “Pocket Calculator” becoming a temporary obsession of mine with all its playfulness and infectious whim. I would lose myself every time I heard the main melody off “Computer Love” – a track that I still hold dear even now – and a song like “Numbers” felt so alien to me upon first listen thanks to its impeccable merging of cold yet commanding drum machine and disorienting synths. At a time where electro house and dubstep were blossoming towards their mainstream peak, I became appreciative of Computer World (and, in turn, Kraftwerk) due to their incessant creativity and inventiveness, especially considering the year of its release.

In a way, it’s an album that never loses its sense of wonder for me, and I think that’s mainly attributed to their dated yet advanced sound, as paradoxical as that may seem. Putting aside its prophetic depiction of the commodification of technology (and all that entails), Computer World sonically feels like music from the future, sans the overwhelming bleakness that’s unfortunately attributed to it nowadays. Each track brings its share of novelty and awe that’s effortlessly captivating no matter when and where you listen to it. Simply put, the record is a portrait of that cautious optimism ascribed to the potential of human capacity.

This goes without mentioning the massive influence Kraftwerk has instilled upon popular music with Computer World, which honestly merits an article in and of itself. Apart from the electronic music scene and the emerging new wave genre that followed its release, the album has crossed paths with the likes of artists such as Fergie, Coldplay, and LCD Soundsystem, and the unlikely affinity between it and hip hop is something to behold (again, a conversation that merits its own article).

It can be argued that Kraftwerk have released other, much more influential records throughout their career (all of which are worth your time!), yet Computer World is ultimately the one I keep coming back to – it’s a comfort album of mine, I might even say. Additionally, while the German act never quite lost their touch with the futuristic since their inception, I can confidently say that Computer World is the one that properly invites you to the future in all its immersive spectacle.

Rush – Moving Pictures

released February 12 1981, by Anthem Records

revisited by David Rodriguez

You can already hear it, can’t you?

‘A modern day warrior – mean, mean stride

Today’s Tom Sawyer – mean, mean pride’

Or what about the wicked synth solo after the second verse/bridge?

Doo-doo doo-doo doo-doo, doooo-doo doo-doo doo-doo

To me, we can’t talk about ‘80s rock without talking about Rush, but really that mostly boils down to Moving Pictures, which came fast, hard, and early (ha) in 1981 and set a bit of a precedent with what Rush would do in the decade of retrofuturism and what oddball directions others would take popular music as well.

While I only have the benefit of hindsight and many, many album remasters to go off of, it was apparent by this time that music was changing. There was additional clarity, texture, timbre, and more in all music. More than ever, atmosphere and the way songs were produced were adding to the experience and definition of music. You can just tell you’re listening to an ‘80s song even if you’ve never heard it before and are familiar with the defining aesthetics. Rush both played into (Power Windows, holy shit) and eschewed those sorts of tenets (literally everything before Power Windows), but nothing was more pronounced and bold as Moving Pictures was.

Rush were responsible – just as Pink Floyd were before them – for sneaking progressive tendencies into digestible, approachable music without compromising time signature changes that I can’t even explain, interesting structures, heightened concepts, and more. At this point, “Tom Sawyer” is an indomitable classic and by far the biggest song Rush ever released. We also got the fan favorite instrumental “YYZ”, which is one of the most expressive tracks the trio ever put down, even making it into Guitar Hero II at the height of popularity of rhythm video games. It’s by far the fastest overall track on the album and, to my memory, one of the fastest they’ve ever released, the intro rhythm (from Neil Peart’s tinny chime strikes to the first riff from both guitars) of it being morse code for ‘YYZ’, which is the IATA airport code for Toronto Pearson International Airport.

“Limelight” helps round out Moving Pictures’ more radio friendly fare with an upbeat song about fame and its sundering of any personal privacy that comes with it – ironic, as it’s on the album that inarguably brought them the most fame. The rebellious “Red Barchetta” has some of Rush’s most iconic guitar and melody work, with Alex Lifeson crafting some gritty riffs for verses, but still injecting an airiness into his fretwork to accompany Geddy Lee’s inimitable falsetto vocals.

The last half of the album – “The Camera Eye”, “Witch Hunt”, and “Vital Signs” – all compose expected Rush deep cuts (even though the latter was a single), all unique in form and specific execution, which makes for a stylistically cohesive album that dares to be dynamic. You know, like prog rock should be. It goes to show that even one of the most progressive rock bands in history knew how to play the pop game on their own terms, and they had earned their chance to do something with their immense talent after putting out untouchable classic albums like the ones I mentioned before. For some, Moving Pictures was the start of a legacy – for the diehards and Rush themselves, it was the solidification of it.

On the other hand, this album was the last time Rush wrote and released a song over ten minutes long, something that had been a tradition on nearly every album since Caress of Steel. In fact, you can count on one hand the number of songs over seven minutes long on their albums since Moving Pictures, and they’re both on their last studio album, Clockwork Angels (they’re all right). Size isn’t everything, but given that some of their best tracks ever were long-form progressive suites like “2112”, both “Cygnus X-1” tracks, and “Xanadu”, it’s hard not to notice.

Their next album Signals would follow a year later, and while it didn’t have quite the heft of Moving Pictures in terms of musicality or popularity, it’s still quite fondly looked upon thanks to songs like “Subdivisions” and “Digital Man”, which did seek to channel that catchiness and instrumental weight balance that this album mastered. It sold immensely well, too. Rush were able to do whatever the hell they wanted to from that point on, and they did to varying degrees of success and artistry, but you can always tell a Rush song when you hear it. That’s largely due to not only their unique style that spans decades, but just how ubiquitous they became because of this one album.

Rush was no doubt a wavemaker in the years prior – 2112, highly considered to be their magnum opus, was a Canadian chart topper; Fly By Night and Permanent Waves earned similar top ten positionings as well, along with very respectable places on the US charts, and there was always deeper cuts like Hemispheres that didn’t fuck around on the prog for us weirdos (I say this metaphorically because I wasn’t even close to being born yet). And while some of those weirdos say this album was their ‘black album’ moment of mainstream coddling, Rush would not be as big as they are now were it not for their meteoric smash breakthrough of Moving Pictures.