‘To Pimp a Butterfly is both Kendrick Lamar’s answer to the tough questions life confronts us with and questions of his own many of which ultimately remain unanswerable.‘

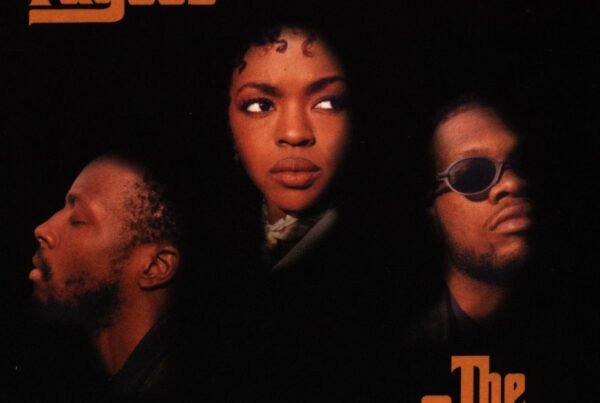

Release date: March 15, 2015 | Top Dawg Entertainment / Aftermath / Interscope | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | Website

Some records are built different: they hit the right nerve at the right time, sparking the emotions and imagination of those caught in their wake, inspiring a creative and/or political boom. To Pimp A Butterfly by American rapper Kendrick Lamar is one of those records. When it dropped in 2015, it sent shockwaves not only through the hip hop scene, but the music world as a whole, one whose effects are still felt today.

Adam P. Terry

The first thing I need to talk about is the beginning of the album. It is uncomfortable, but given the George Clinton sample on the intro it is unavoidable. It’s literally one of the first words heard on the record and it hits hard. Especially given the modern convention to mostly steer away from that hard ‘R’. Better to just briefly address it at the outset.

That word. It is so uncomfortable in these opening moments of the album. And it’s not just because of my white guilt at consuming black media. Though that is part of it. But more so because it is important. And it is powerful. It is the most powerful word in the English language. But it cannot be ignored. Things are uncomfortable when they lack context. And who better to provide that context than Kendrick Lamar himself. From the opposite end of this very album off the penultimate track “i”.

‘Sound like I needed some soul searching/My pops gave me some game in real person/Retraced my steps on what they never taught me/Did my homework fast before government caught me/So I’ma dedicate this one verse to Oprah/On how the infamous, sensitive N-word control us/So many artists gave her an explanation to hole us/Well, this is my explanation straight from/Ethiopia N-E-G-U-S definition: royalty; king royalty—wait, listen/N-E-G-U-S description: black emperor, king, ruler, now let me finish/The history books overlooked the word and hide it/America tried to make it to a house divided/The homies don’t recognize we been usin’ it wrong/So I’ma break it down and put my game in a song/N-E-G-U-S, say it with me, or say it no more.’

This is the crux of the issue. That word is powerful both when it is used in solidarity and misused in hate.

The second thing I need to talk about is the ending of this album. The entirety of To Pimp a Butterfly is essentially a love letter to Tupac Shakur. This is something that I somehow completely missed ten years ago. I was lost in a forest of sonic landscapes. I still am. Each song ends with verses of a poem that Kendrick has composed and embedded throughout Butterfly. Cleverly the last line of each section directly ties into the thematic concern of the next song. I won’t go into detail further here, a whole dissertation could be written dissecting the brilliance at work. I will however point those interested to an excellent summation from the hiphopheads subreddit.

Ultimately the poem is recited in full on the final cut “Mortal Man”. A 12-minute epic closing track. Part song, part spoken word, and part facsimile of an interview that never happened and a larger conversation that is still happening. Whenever I first let this album flow over and through me I was drowned, awash in sounds. I didn’t even recognize that this WAS Tupac. Like not just a character or a skit. This is literally Tupac speaking, taken from an interview which Kendrick went back and wrote questions to. Masterfully editing everything together to create a complete narrative. All the thematic concerns and social commentary which comprised the previous hour and six minutes is fully realized in the final twelve.

To Pimp A Butterfly cannot be fully understood without this context. Questions of power, identity, and legacy are central to any informed reading of the text. And perhaps more so than any other rap album Butterfly IS a text. To be read, studied, and appreciated as such.

Flash forward to today and Kendrick is flying high in 2025. Fresh off of a decisive victory in THE rap beef of the era, he surprise dropped his new record GNX which is an onslaught of banger after banger of flexes and shots fired. Then he goes on to perform the most-watched half-time show in NFL history and first by headline by a solo rap artist. At this point his legacy as the GOAT is pretty well cemented. Fuck a Top 3. Drake and J.Cole can clutch tightly to their sales and streams. When it comes to quality and consistency no one else comes close to Kendrick and Tyler, the Creator.

To further the point and secure Kendrick’s legacy one need look no further than debates over the greatest rap album of all time. After 36 Chambers and Liquid Swords these quickly devolve into an argument over which is better: Good Kid, MAAD City or To Pimp a Butterfly. Both Kendrick joints are fully GOATED. It’s essentially a question of preference as they are both near perfect records. Like Igor vs Flower Boy it’s really just a matter of taste. For myself I’m Butterfly and Flower Boy all the way. But all four records are modern masterpieces.

Looking backwards again, legacy was central in mind when Kendrick conceived of and began construction on what would become Butterfly. After a journey to South Africa the year previous he was feeling connected to his roots and ready to explore a wide sonic collage. Looking upward to Tupac and his legacy as well as the influence of soul, jazz, blues, reggaeton, and afrobeat are key to the unique soundscapes of Butterfly.

The next core concern of Butterfly is identity. Identity as a black man. As a rapper. As a kid from Compton. As a celebrity. All of these burdens are shared between Kendrick and Tupac. Looking backwards now more informed this time around it is easy for me to see how Tupac is the heart and soul of this record.

At the beginning of the record when Kendrick asks ‘Gather your wit, take a deep look inside/Are you really who they idolize?’, it is a question of identity. On “Blacker the Berry” when he says he is ‘The biggest hypocrite in 2015’, it is a question of identity. On “Hood Politics”: ‘Everybody want to talk about who this and who that/Who the realest and who wack, or who white or who black/Critics want to mention that they miss when hip hop was rappin’/Motherfucker, if you did, then Killer Mike‘d be platinum!’ Identity.

At the end of Butterfly asking ‘When shit hits the fan, is you still a fan?’ Are you ride or die or just a fair weather faker? What is the true identity of the artist and what is your identity as a fan? This is a multilayer inquiry into multifaceted relationships. Kendrick’s identity as a young man coming up in Compton as a fan of Tupac. His identity now as the masses are suddenly looking up to him. Or looking at him under a microscope lens of criticism.

Central to this question of identity is fame and celebrity. How do you stay true to yourself under all that pressure? What does the weight of all those eyes constantly on you do to a person? Do you live up to expectations or fall short?

‘I’ve been dealing with depression ever since an adolescent/Duckin’ every other blessin’, I can never see the message/I could never take the lead, I could never bob and weave/From a negative and letting them annihilate me/And it’s evident I’m moving at a meteor speed/Finna run into a building, lay my body in the street/Keep my money in the ceiling, let my mama know I’m free/Give my story to the children and a lesson they can read/And the glory to the feeling of the holy unseen/Seen enough, make a motherfucker scream, ‘I love myself!’’

The final piece of this puzzle is power. Most often who has it and who doesn’t. And most critically how it is used or misused. Power is explored and critiqued throughout the record but perhaps nowhere more so than on “Hood Politics”:

‘Streets don’t fail me now, they tell me it’s a new gang in town/From Compton to Congress, set trippin’ all around/Ain’t nothin’ new, but a flu of new Demo-Crips and Re-Blood-licans/Red state versus a blue state, which one you governin’?/They give us guns and drugs, call us thugs/Make it they promise to fuck with you/No condom, they fuck with you.’

This feeling that it doesn’t really matter who is in power as they are really just two sides of the same coin. Ultimately they will never represent anything but the rich and powerful while the poor and disaffected are left on their own. Who speaks for the powerless? Who represents them?

In parting I’ll leave off with one final tidbit: the original title of the project was To Pimp a Caterpillar (T-PAC). The symbology of both caterpillar and butterfly are at work throughout the project. And summarized in the final moments of the album as Kendrick finishes his interview with Tupac relaying to him the story of each.

‘The caterpillar is a prisoner to the streets that conceived it. Its only job is to eat or consume everything around it. In order to protect itself from this mad city. While consuming its environment, the caterpillar begins to notice ways to survive. One thing it noticed is how much the world shuns him, but praises the butterfly.

‘The butterfly represents the talent, the thoughtfulness and the beauty within the caterpillar. But having a harsh outlook on life, the caterpillar sees the butterfly as weak. And figures out a way to pimp it to his own benefits. Already surrounded by this mad city, the caterpillar goes to work on the cocoon. Which institutionalizes him. He can no longer see past his own thoughts, he’s trapped. When trapped inside these walls certain ideas take root, such as Going home, and bringing back new concepts to this mad city. The result? Wings begin to emerge, breaking the cycle of feeling stagnant. Finally free, the butterfly sheds light on situations that the caterpillar never considered. Ending the internal struggle. Although the butterfly and caterpillar are completely different. They are one and the same.’

Kendrick asks Tupac what he thinks of that. And tragically there is no response. The album ends. There can be no reply because Tupac is gone and we are left to ourselves to interpret and attempt to make sense of the world around us. To Pimp a Butterfly is both Kendrick Lamar’s answer to the tough questions life confronts us with and questions of his own many of which ultimately remain unanswerable.

Alex Eubanks

I’d say it’s not uncommon for an artist’s best work to haunt them in at least some capacity. Normally it comes in the form of the struggle to live up to your best, especially when it comes early in your career. People always want the old hits, not as interested in the new work, hard to switch styles, and after all it’s always possible they did just manage to peak early. It can be tough.

With Kendrick coming off his victory lap from winning maybe the biggest rap battle ever, it’s fascinating to go back to To Pimp a Butterfly and see how Kendrick’s best has impacted his career.

It’s just hard not to listen to this and not see how Kendrick did it to himself with the savior labeling that he’s been trying to reject ever since making TPAB. There are certain things that Kendrick loves to play both teams on (his hatred of people that neglect their children or ‘like em young’ is definitely inconsistent to say the least) and he absolutely does love to play the savior when it works for him and he can control the narrative but he hates when that label is applied by others. I think this is going to be something he wrestles with for his entire career.

Are some of the things that get forced onto him as a result of these tendencies fair? No. For example, I think that since TPAB dropped there’s been a small but vocal among critics especially who have this idea of a Kendrick album that they want him to make where he… I guess saves race relations across the globe or something? They never articulate what they want, but they’re always unhappy he’s not fulfilling their fantasy. DAMN. essentially exists to reckon with this labeling and change in treatment and Mr. Morale shows how much it still bothers him.

He’s not the first celebrity to challenge society, or the government, or the entertainment industry, but he is one of the most effective at it, which makes it a bit unfortunate he shares some of the same habits that other celebrities do where they want to pull away when fans look to them to keep using that platform. I don’t expect Kendrick to stop the challenges though, and I don’t expect people to stop putting him on a pedestal either. The cycle continues.

If I had to guess, I’d say that Drake’s attack on Kendrick as the ‘black messiah’ on “Family Matters” was one of the few things that actually got to him. He hasn’t stopped saying those types of things bother him since 2015 after all.

It also definitely gets under his skin that Drake isn’t the only one who thinks like this. Drake has a legion of fans that share in his mindset that an album like TPAB is boring and ‘tryna get the slaves freed’, and Kendrick strikes me as the type that lies and says they aren’t online but actually is reading everything they can possibly get their hands on. It’s definitely why he’s on three Carti tracks, and why GNX has so many immediate bangers. I think he’s very aware that this album poisoned the well for some people. TPAB making conservatives more vocal about him because they now knew who he was; that was expected pushback, but I doubt that he saw it coming how many people would just reject him off his style. Has he won in the end? Yes. But it clearly was a process that took a lot out of him and the negative feedback has really impacted him more than most others respond to theirs.

With that said, I still love this album. I’m not smart enough to give you the in-depth lyrical breakdown for the album though soI won’t do it. Also, it’s been 10 years and it would make me double the length of this section. If you haven’t done a deep dive on one of the most complex, layered, and rewarding albums ever made, it’s on you.

There’s still so much of the small things about TPAB that I just fucking adore. I think Kendrick’s rapping in the last 45 seconds of “Momma” is probably my favorite from him ever. It’s so simple and quick, yet the production and the way it sounds as it slowly fades out without ever really cutting is so fucking perfect to me I just can’t get enough of it. Interludes can be very hit or miss for me, often more miss than hit, but “For Free?” and “For Sale?” are two of the best I’ve ever heard. It’s hard to recall another project with just one interlude this meaningful and this well done. “For Free?” may be the more popular of the two with the still iconic ‘this dick ain’t free’, but I think the extra depth Kendrick gets on his music industry and rap critiques on “For Sale?” makes it a bit better of a relisten. That narrative continues a bit on “How Much A Dollar Cost” detailing Kendrick’s (mostly) real encounter of someone asking him for money while in South Africa. It’s an incredibly powerful song to look back on and the ending works every single time you hear it.

This may just be me, I know “King Kunta” has long been held as the ‘Drake diss’ from this album but I feel like “You Ain’t Gotta Lie (Momma Said)” is much more targeted and frankly meaner. I’m not trying to take you too far behind the curtain, and if the shoe fits and all that, but Drake is far from the only mainstream rapper who uses ghostwriters. You’re gonna have to narrow a ghostwriting diss down. ‘And the world don’t respect you,/And the culture don’t accept you/But you think it’s all love/And the girls gon’ neglect you once your parody is done/Reputation can’t protect you if you never had one.’ Now that’s targeted.

Also gotta take a minute and acknowledge how much of a ballsy decision the album version of “i” is. Before the last twelve months vaulted Kendrick to a new place of commercial success, “i” was and to an extent still is one of Kendrick’s bigger tracks. It’s in movies, trailers, video games, commercials, you name it. It’s very catchy and easy to listen to, and while “alright” and “King Kunta” grew past it, it was the biggest single leading up to the album and that version isn’t on the album. The album cut’s much more raw and unrefined live-ish quality version is such a bold creative choice, especially considering it’s not the entire track, and Kendrick cuts himself off mid-song to give an anti-violence speech to the live listeners. There’s only one Kendrick for a reason.

It’s been well-documented how lyrically special TPAB is, how timeless and flawless the production is, and the perfect supporting cast, but one I don’t see mentioned often is how rap was right on the cusp of a small jazz rap resurgence that made Kendrick’s timing for this album perfect. He didn’t have to create a foundation from scratch, there were a handful of artists around his age that had already had mainstream success, and yet doing this would still place him ahead of the curve by a good bit. Robert Glasper, Thundercat, Knxledge, and Flying Lotus (there are so many more artists that contributed to the production work) all had reached a level of fame where they were established but not household names yet. Others like Anderson .paak had helped set the groundwork for the resurgence and obviously Kendrick got a number of vets like George Clinton, Bilal, and Pharrell to help as well.

I wouldn’t necessarily credit Kendrick with the brief spike for what had been a bit of a dead subgenre at the time though. Music, like most things, is cyclical and there have been smaller comebacks before. Can’t say he was responsible for the greatest act in the subgenre’s history (A Tribe Called Quest) coming back after nearly 20 years away and dropping an all-timer the following year – he was on it though. He was responsible for the fact that almost everyone associated with this had a spike in popularity which gave more attention to some of the quality releases they put out next. Others like .paak, Mac Miller, and Noname had been doing cool stuff with the genre as well. It was a fun wave, I hope there’s another soon.

The production on TPAB just feels so timeless. It’s part of the reason there was the new wave in the first place, the sound never went bad in the way some subgenres have where after like 18 months you feel like everything has been done that can be done.

When I think of To Pimp a Butterfly the first thing I think of is the beat to “Wesley’s Theory”. It’s maybe the best instrumental I’ve ever heard for anything, I completely adore it. The Flying Lotus and Thundercat foundation of the track is incredible and the Sounwave extras and samples make the beat legendary. “King Kunta” almost matches it – it’s one of the catchiest tracks you’ll ever hear and Sounwave again killed it.

“Hood Politics” has Thundercat’s hands all over it, the beginning intro strumming is incredible, he’s one of the best bass players ever. The sound and style shift on some of the album’s darkest moments is remarkable as well. “u” starts off very uncomfortable, and the more Kendrick vents about his own self-hatred and insecurities the more the horns and playing descend into full-blown anarchy – I don’t think anyone else could have rapped over this. The only time the album’s jazz style is abandoned is for another bleak-as-hell track in “The Blacker the Berry”. It’s much more of a boom-bap throwback in the vein of some of Nas’ darker moments, it’s a real interrogation of racial violence and its comparison to gang culture. Hell of a single by the way.

TPAB also has a rare honor where it’s a complete 1-of-1, and there has essentially been no real effort to recreate it. Most of the time if a big artist puts out an album this successful it’ll almost immediately spawn a wave of imitations, yet everyone seems to have (correctly) decided that you’d have to be a fucking moron to even attempt something like this again. Imagine Rick Ross trying to pull this off. He’d get laughed out of the room.

And that’s part of what makes TPAB such a special album, not just among Kendrick’s discography, (and I would say that this is without much doubt his high point) or in rap, but in music as a whole. There are very few works that are truly unique and irreplaceable and this is one of the few. No one else could have done this, no one else should try, and we’ll never hear anything like it again.

Broc Nelson

There are few rappers capable of making albums like Kendrick Lamar. Since 2015’s To Pimp a Butterfly, this has been undeniable, and K-Dot has become my favorite active rapper. Prior to 2015, he was in the running. g.O.O.d Kid m.A.A.d. City was a monumental achievement. Framed like a tumultuous coming-of-age film about the struggles of growing up in Compton, the temptations and peer pressure that surround the protagonist as he navigates an often-hostile terrain. Burdened by teenage lust, the hustle to stay afloat, family issues, and more were told through each song with a remarkable economy of words, changing flows and beats, and all of the accompanying drama while still cranking out bangers.

Making an instant classic that is also a concept album is a rare feat, but for all of the cleverness Kendrick displayed on m.A.A.d. City, he was also lending his voice to guest verses, unapologetically. He still does this, despite it being a bit a faux pas. Traditionally, when MCs guest on another artist’s track, the goal is to make the lead artist look good. Kendrick has like, zero interest in this, and every bar he has spit since section.80 has been out for blood, to prove he is the GOAT.

So, when To Pimp a Butterfly came out, I immediately put it on expecting greatness. What I didn’t expect was the level of greatness he delivered. TPAB is the kind of album that shakes a generation. Favoring funk and jazz over the prominent trap and boom bap with S-tier musicians like Thundercat, George Clinton, and Kamasi Washington was enough of a reason to be floored by To Pimp a Butterfly, but the Compton Kid wasn’t done with the concept albums. And that is where the biggest impact came from.

On the surface, To Pimp a Butterfly is about rising to stardom. Like his previous album, Kendrick is faced with navigated a morally nihilistic world as a man of principles, but this time the setting is fame, success, and the music industry. These things are the pimp, Kendrick and his talents are the butterfly having emerged from the Compton caterpillar and cocoon. Cool, yeah, but many hip hop albums share the theme of coming to terms with newfound wealth and fame. Kendrick adds another layer to it, though. The exploitation of Black artists comes from the entertainment industry’s participation in AmeriKKKa’s historically racist capitalism.

I’m not going to spend time unpacking that. There are numerous books about how fucked up the United States is and a lot of books about Black history and racial justice will give you those answers if you wish to protest. For the sake of this piece, we are going to focus on the content and ideas that Kendrick Lamar is working with on this album, and he has definitely taken these ideas as fact. So shall we.

“Wesley’s Theory” kicks off all of these ideas. The first verse personifying hip hop as his first girlfriend and describing everything he will buy with his newfound wealth. The second verse told by Uncle Sam (a theme repeated during the Super Bowl performance) laying bare the insidious nature of American capitalism and consumerism. Buy whatever you want, consume and perform for your bigger share of the peanut bag. Uncle Sam is going to get you in the end. You are not free.

“Wesley’s Theory” is a great track, but “For Free?” is the track that made my jaw hit the floor. A few months after TPAB came out, I was sitting with a shift beer (or three) at the brewery I worked for. An ex-Marine that I was acquainted with came in with a girl. She proceeded to play “For Free?” on the jukebox which quickly made the Marine guy pissy. ‘I don’t want to hear about how big this guy’s dick is!’ he exclaimed, calling the song garbage. Tipsy me shot back with some version of this:

‘This song isn’t a boast about Kendrick’s dick, nor is it a condemnation of women demanding material goods for sex. This song is about how consumerism drives how we relate to each other, that despite success or wealth, a Black man in America is still enslaved to whatever white ownership he serves under, whether or not they feel free about it, how the white man’s greed alienates and monetizes everything, down to sex and relationships and self-perception of our own genitalia, and how all of that wealth and power was built through unpaid Black labor. So, chill with your assumptions.’

Dude just said, ‘well Goddamn, Broc,’ and he and his date sat in awkward silence until they finished their beers and left. This song may be why I enjoy raps without hooks. It is more slam poetry than it is a traditional song, but overall it absolutely rules. Ten years later, “For Free?” still gives me chills.

“King Kunta” comes next, and was probably my favorite song on the album at the time. For the casual listener, it is another hip hop boast track, but Kendrick is also alluding to the show Roots (Kunta Kinte), Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (referencing yams, also an allusion to Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart), James Brown (‘I can dig rappin’’), as well as Dogg Pound and Michael Jackson. Literate fucking layers running bars around any other MC, the power of this man’s throwaway lines is deeper than anyone else on his level of popularity, and it isn’t even close. This song also kicks off the first Drake sneak diss, ‘a rapper with a ghost writer?/what the fuck happened?’

There is a whole lot more of this album to cover, and we can see how nuanced and layered To Pimp a Butterfly is, already. Full analysis of everything going on here could fill a book, so I will touch on a couple more things in the interest of brevity.

First, let’s look at “The Blacker The Berry.” This song is a fucking emotional warhead, for me. I am white. I was raised in a very white environment, but at an early age I began to recognize the dangers of racism, how it must be built on ignorance. As I grew and began to witness more and more Black people being killed by the police, seeing racist groups still active, seeing how white people don’t acknowledge race or learn about racism as a system and not individualized bigotry, or how in our own segregated and isolated bubbles we inherit racism, microaggressions, learned and nurtured thought patterns that at the very least continue to enable racism if not impact whatever well-meaning thoughts we have about race by negating them with assumptions and unchecked behaviors.

So, I again recommend reading and learning about racism to unlearn these socially inherited issues that you may not be conscious of, but I say all of this to put into perspective how much this song punches me in the gut. Coming after the song “Complexion,” whose hook is ‘complexion don’t mean a thing,’ “The Blacker The Berry” addresses racism and colorism head-on, aggressively. ‘I’m the biggest hypocrite of 2015,’ he begins each verse. The first two verses decrying racism in straightforward terms. The impact of these verses alone is enough to scare suburban and rural white folks into checking themselves, how do we criticize violence in and between races? What gives us the authority ro make those judgments? How does the oppression of Black communities perpetuate violence through economics? Why do ‘successful’ people deserve more respect for having muscle cars or other signs of wealth?

Amidst all of these questions and accusations, Kendrick continues to paint himself a hypocrite and exposing that the generational hatred, the forced competition of Black people through the shackles of racism have lead to tribalism and violence amongst gangs. ‘Why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street when gang banging make me kill a ****** blacker than me? Hypocrite!’ the last line landing like a slug to the chest. This song doesn’t condone Black on Black violence or use that tired line to absolve white people of their own racism, but manages to look at racism and bigotry and colorism from all angles. The driving beat and fierce delivery add to the impact.

Conversely, “Alright” is a song of hope. Hope that through community and faith these long held struggles can be resolved or at the very least, survived. ‘Alls my life I had to fight,’ Kendrick starts in yet another literary allusion (Alice Walker’s The Color Purple), repeatedly letting us know that racism in the United States is ingrained in our history. Since the first slave ship landed in 1619, every moment of Black existence in the United States has been a fight for freedom, for equity, for justice. In fact, every struggle for liberation and rights in the United States was fought first by Black people, and as we traverse 2025’s backsliding into more oppressive territory, we should look to those movements and struggles.

“Alright” became an anthem for the Black Lives Matter movement. It will probably stand as the biggest track from TPAB because of this, and I will not argue that it shouldn’t. Hope has always been more appealing than facing the gritty realities of actual struggle, but songs like “The Blacker The Berry,” “Institutionalized,” “u,” and “For Free?’ that expose the more challenging sides of racial justice, self-doubt, personal shortcomings, and the parasitic nature of capitalizing off of other people’s labor lay the groundwork for how hope has to be an act of revolution, internal, external, and social revolution. Hope cannot remain a passive feeling of longing, it must come from the darkness like a righteous beacon to guide anyone involved in liberation movements through the grimy, gritty, and discomforting realities that we face. So, as the record companies, radio stations, streaming services, and even Kendrick Lamar himself rake in the dough through this song, may the hope you feel from it flow through your whole body, because protest songs don’t mean shit if they are sterilized into feel-good sound bites.

Anyway, To Pimp a Butterfly deserves more page space than I can responsibly fill here and now. The complexity of the music and lyrics are on par with the greatest poets and novelists throughout history. Kendrick Lamar may have won a Pulitzer for DAMN., but I am convinced it was really because it was too late to recognize TPAB by the committee that year. Like Curtis Mayfield, Stevie Wonder, Sly & The Family Stone, War, Prince, and others, Kendrick Lamar created one of the most powerful combinations of pop and politics in recording industry history. Whether you love it or hate it, to deny the cultural impact of this album is foolishness of the highest order. All political and jazz inspired hip hop from 2015 onward will have to compete with this album, and it will likely be a long time before anything comes close to overtaking its status.

So, please revisit this album. Read other, more competent and detailed analysis of it. Read the books Kendrick references. Read more books beyond that about racial and economic struggle. Let these things empower you, and if you act accordingly, we are going to be alright.