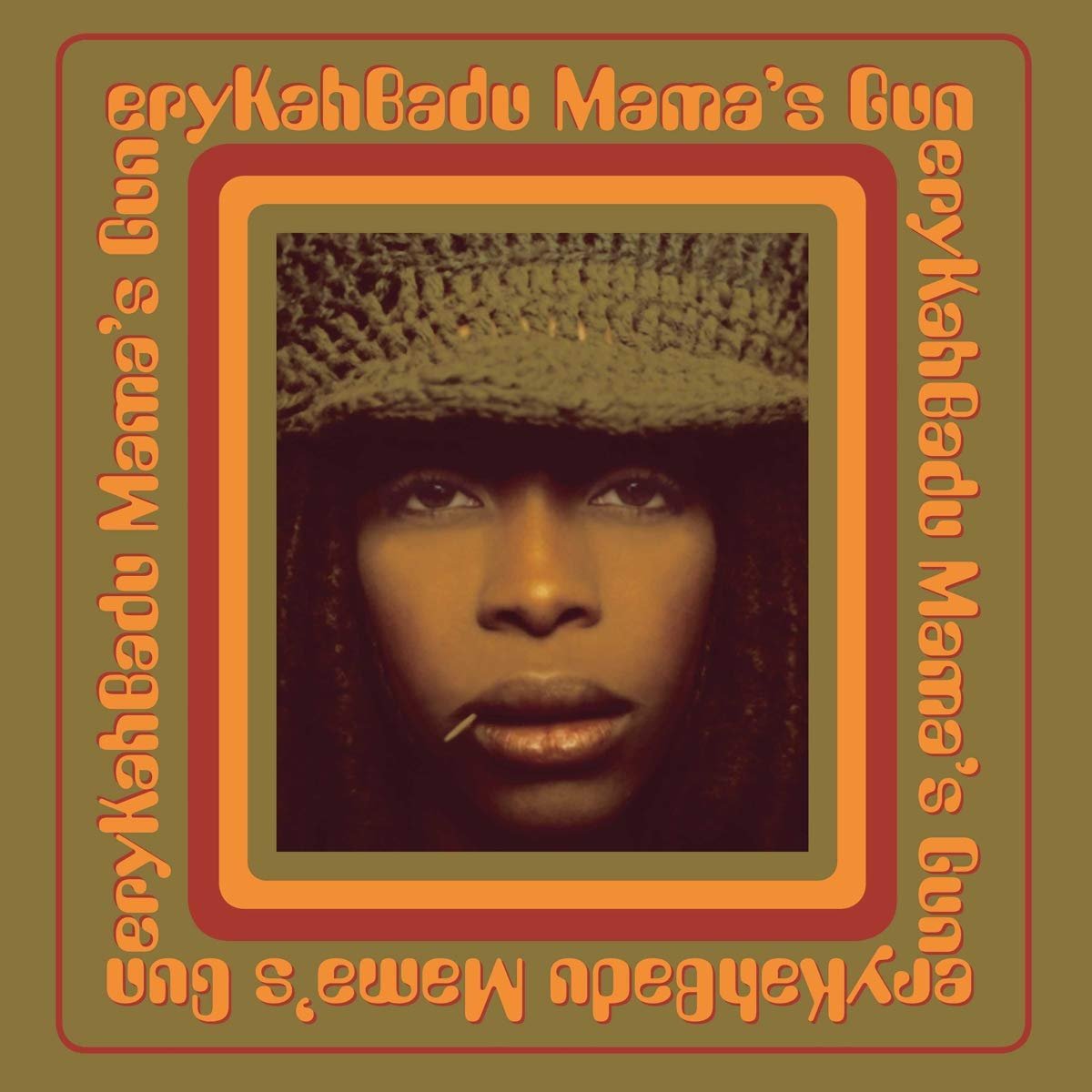

Miss Erykah Badu, first lady of neo-soul and one of the strongest, most determined voices to emerge in the latter parts of the 90s. This should be introduction enough – indeed, this woman’s reputation cannot be overstated. After almost 21 years since its release, her sophomore release Mama’s Gun has lost none of its luster; you may even argue that it shines even brighter today than it did back in the year 2000. In order to properly celebrate this album, EIN staffers Tyler and Charles have come together to offer their perpectives on Badu’s work and the importance it holds in the (modern) soul canon.

Charles Stinson

In the mid 1990s I was a young hip hop head, and the burgeoning neo-soul movement had triggered my interest in other Black American genres of the past. It was a sound rooted in soul and incorporating funk, jazz and hip hop, and it was unafraid to embrace rock and electronic music. Erykah Badu was one of its pioneering artists. She was a beautiful, free spirit sipping herbal teas and burning incense, adorned in colourful headwraps; her 1997 debut, Baduizm, was a gorgeous blend of soul and jazz with hip hop sensibilities. It was intoxicating.

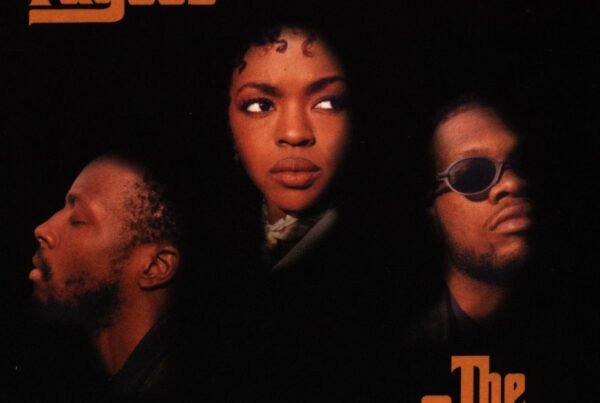

The endless comparisons to Billie Holiday led me there first, and then to other jazz artists, and eventually to soul and funk. It was a musical awakening for me, and I never stopped exploring. Meanwhile, neo-soul was expanding its boundaries to include ever more influence from the hip hop I had come up with, culminating in the 1998 classic The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.

It was around this time that D’Angelo had recruited Questlove and recording engineer Russell Elevado to work on his follow-up to Brown Sugar – often considered the first neo-soul album. What transpired over the next few years was nothing short of magic. Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios became a magnet for like-minded musicians – a who’s who of experimental black artists steeped in the history of their forebearers, but who were pushing the music to new places. The Soulquarians, as they became known, was a musical collective that included Questlove, D’Angelo, J Dilla, James Poyser, Mos Def, Common, Q Tip, DJ Premier, Bilal, Roy Hargrove, and Erykah Badu among others. They were the most creative musical minds of a generation, spanning the gamut of black music, from soul and r’n’b to hip hop and jazz.

Over the course of five years, they would gather at Electric Lady to hang out, eat, watch movies, and geek out on old concert footage of Prince, Al Green, Marvin Gaye, and Sly & The Family Stone. When the inspiration moved them, they would eventually pick up their instruments and jam.

The sessions were recorded to two-inch tape using the same analog equipment that had recorded Jimi, The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and Stevie Wonder. There were thousands of hours of tape; much of it was throwaway jams and covers, but buried in there were countless moments of magic that would be divvied out to whoever claimed them first. What I wouldn’t give to get my hands on all that tape that never got published!

Over the next few years, the records started to take shape. Each artist would bring their own flavour – D’Angelo’s Voodoo was a masterpiece of soul; The Roots made their experimental hip hop opus Things Fall Apart and the rock-hip hop fusion of Phrenology; Common recorded Like Water for Chocolate and the futuristic Electric Circus; and Erykah Badu made the extraordinary Mama’s Gun.

From the outset, it’s obvious that Mama’s Gun wasn’t going to be an effort to recapture the commercial successes of Baduizm. “Penitentiary Philosophy” hits you with a wall of sound – swirling organs and guitars surround the abrasive rhythm section, sounding more like Maggot Brain-era Funkadelic than neo-soul. While Baduizm was all hippy vibes and jazzy grooves, Mama’s Gun was the sound of something much more sinister, comparatively unstructured and full of thick, meandering funk jams.

It would be hard to overstate the influence J Dilla on this record, and on the soulquarian sound in general. He was notorious for turning off the quantization on his drum machine, creating a groove that depended on timing inconsistencies. His signature sound is all over the record – on “Didn’t Cha Know”, he loops a bassline, sampled from Tarika Blue’s “Dreamflower”, and drenches it in wah, wah keys and percussion; on “My Life”, he creates a beautiful piece of r’n’b.

Beyond Dilla’s direct input though, his sound is evident throughout. Questlove spent years recrating Dilla’s timing inconsistencies on his drum kit. He had to unlearn the precision he mastered for hip hop, which relied on machine-precision for its drums. He would delay his snare sporadically to create an off kilter, ‘drunken’ rhythm. On the live kit, with Pino Palladino on bass, the result is infectiously groovy, and this sound is central to almost everything on Mama’s Gun.

The bohemian Badu still appears, most notably on the previously mentioned “Didn’t Cha Know”, and on “… & On”, a reprise of the Baduizm hit “On & On”. But even here the contrast is plain to see. In comparison to it’s predecessor, “… & On” has a dirtier sound, with a head-nodding hip hop feel and a great jazz breakdown on the bridge.

My personal favourite, “Booty”, shows a more playful side to Badu, who taunts a rival over her boyfriend. A sublime drum break starts it off, J Dilla makes an appearance on bass, and the late Roy Hargrove plays and arranges a great horn section. It’s funky as fuck! Other standouts are “Kiss Me on My Neck”, where the sultry verses break into an early Funkadelic-style jam for the chorus, and “Time’s a Waistin’”, a slow jam groove that you never want to end, with a beautiful string section. For a change of pace, “In Love with You” is a duet with Stephen Marley, and a sublime piece of acoustic soul.

Badu explores various themes on the LP. There’s gritty street tales and paranoia on “Penitentiary Philosophy”; several tracks exploring relationships; self-love and soul searching on tracks like “Didn’t Cha Know” and “Kiss Me on My Neck”; and “A.D. 2000” is a broken-hearted eulogy for Amadou Diallo – an immigrant who was shot by four policemen who were subsequently acquitted – and the song predates #blacklivesmatter by 14 years.

The phenomenal single “Bag Lady” revisits Ntozake Shange’s play For Coloured Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf. Badu recognizes the spectrum of emotional burdens carried by women the world over – from ‘garbage bag’ ladies (the poor) to ‘Gucci bag’ ladies (the rich). She recognizes the ‘paper sack’ ladies (alcoholics) and ‘dime bag’ ladies; and of course, with a toddler at this point in her life, Badu acknowledges the ‘baby bag’ ladies as well. She offers recognition and solidarity, but never preaches. It’s a powerful song.

Closer “Green Eyes” is a ten-minute epic addressing Badu’s recent split from André 3000 of Outkast, who’s the father of her then three-year-old son, Seven. The song has multiple suites capturing the moods of a doomed relationship – jealousy, fear, regret, and eventually resolution.

After rising to the top of the r’n’b world with the smooth, jazz-inflected sound of Baduizm, Erykah Badu immediately explored more experimental ground, and continues to do so today, releasing several fantastic records in the process. But with Mama’s Gun, she produced something truly exceptional.

Tyler Kollinok

Somehow, I’ve never actually listened to a full Erykah Badu record. I grew up mostly in a household that listened to typical radio rock and pop music, so I wasn’t properly introduced to soul until I went looking for it myself. As someone who now claims to love neo-soul music, it’s pretty shocking that I never took the time to listen to Badu’s legendary sophomore album, Mama’s Gun. Fortunately, when I was given the opportunity to write about it, I decided to take the deep dive and finally embrace the epic hour-and-twelve-minute journey it would take me on.

I quickly found that listening through this record is a pretty powerful and touching experience. Badu understands how to write an album that runs through varying moods and emotional responses that don’t rely on staying safe and dull. The excitement of the opening track “Penitentiary Philosophy” is totally opposite from the spacey ballad “Orange Moon”, but both tracks still compliment each other in the grand scheme of the collection. While “Didn’t Cha Know” was the only track I was familiar with before listening to the entire album, I was delighted that the music varied throughout the experience.

This album is 20 years old, but it still feels strikingly fresh and modern to me. Badu is certainly a gorgeous vocalist that understands her vocal range perfectly, but I’m blown away by how clean the record’s production is. I remember having an assignment in a college music production class where we needed to pick an album to use to reference for ‘studio monitor tuning’. If I had known at the time about the impeccable sound on Mama’s Gun, I would’ve picked it instantly. The musicianship is pristine, the many layers make the songs sound full and moving, and the overall quality is exemplary. I may not have a more significant spiritual connection with this record (yet), but I can still feel the passion behind each track.

Erykah Badu is a force to be reckoned with, and it’s obvious why she’s been deemed the first lady of neo-soul. After twenty years of Mama’s Gun, it’s obvious why Badu is still relevant in the music industry, despite not releasing much music in recent years. Although I wish I had been introduced to this album sooner, it’s definitely a collection of music that I plan on continuing to revisist. I may not be a fan of the controversial things Badu has said in recent years (which I honestly didn’t know about until reading through her Wikipedia), but her music is fantastic, and she is an absolute musical genius.

What are your thoughts on/experiences with Mama’s Gun? Are you a fan of Erykah Badu, and if so, what’s your favorite album of hers? Do you have any records you’d like to recommend for inclusion in A Scene In Retrospect? Leave it all in the comments if you feel like sharing!