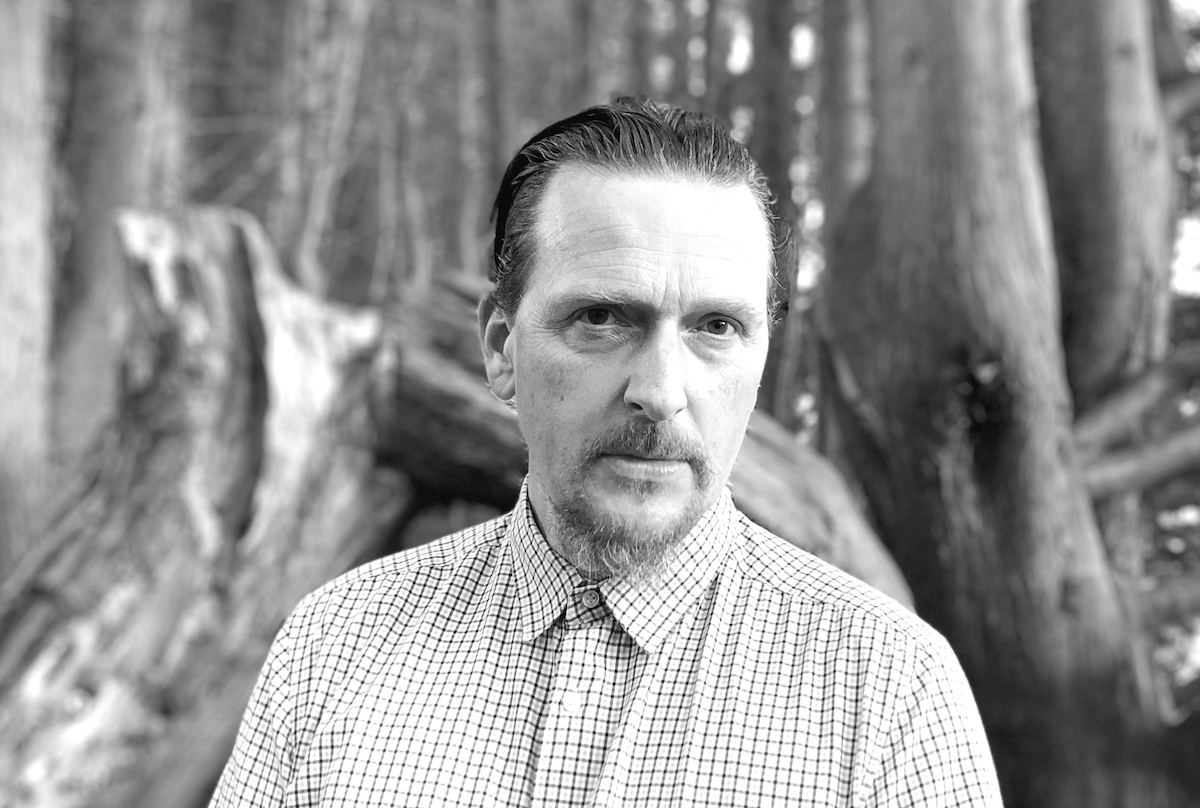

Justin Broadrick’s lifelong ambient drone project Final explores the missing pieces of the world around us on What We Don’t See.

Release date: May 31, 2024 | Room40 | Facebook | Instagram | X | Bandcamp

In the world of Final, the Earth is a living, breathing entity; a seed suspended in space, potential energy bursting at the edges of its shell. If we are patient enough, as humans, we could be the spectators we are meant to be on this giant ball of iron and ore and get out of the way. That way, we could sit back and listen as the world took its time to rebuild and fill the spaces left empty. On What We Don’t See, the latest release from Justin Broadrick’s drone project Final, these sounds ebb and swell, edge and soar and- on brief occasions- seem to pulsate beneath the noise, for a lack of a better term. But that’s the point isn’t it? Artists are always trying to find that better term, a sound that fills the spaces language couldn’t before. Broadrick has been an infamously proficient and dependable producer of those ‘better terms’ for decades now. From his work as a teenager carving out the foundation of grindcore with Napalm Death, or his later re-assembled industrial alternarock in Godflesh, or the more meditative and less accusatory shoegaze of Jesu, Broadrick has been there on the edges of life all along, a career committed to finding a better way of expressing what we all feel.

What We Don’t See is Broadrick’s 18th release by his ambient drone project Final, and in it he invites the listener to meet him in the spots where it’s impossible to meet, the spots that fill up the empty intermolecular spaces that allow us to be in more than one place at one time. It’s about the water rushing in to fill the depressions left from the imprint of our fallen bodies, an erasure of all that came before it. What We Don’t See is the white noise of the 20th century drifting off through the lamp lit streets of the suburbs. Broadrick doesn’t so much build an atmosphere, as he recognizes what isn’t there and tries to fill that up, be it with long, slowly undulating echoes of deeply effected guitar or a low-frequency hum that exists as the tarmac for an ever diminishing greenery. Broadrick, after all, is dealing with an existing infrastructure. It’s his job to fill in the spaces.

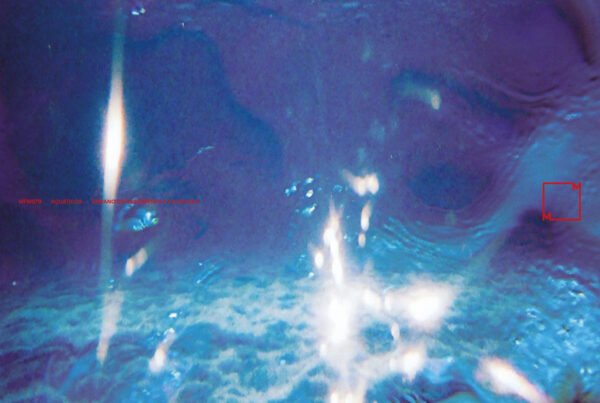

The album opens up with “Bodyless”. A single note drone, oscillating in and out of frequency, washes in and out over the sonic shoreline on which Broadrick starts the journey. A powerful tide moves in, overwhelming, the ocean in a giant exhale of energy. The sun goes down and the water retreats. What was filled before is now empty. What was empty before is now full. Broadrick has described the album as a response to the invisible world around us. How “Bodyless” and the other 7-10 minute drone experiments on What We Don’t See address that void lies mostly in their ability to breathe and grow. Nothing fast happens on Final‘s watch, and while frequencies throb and pulsate, reaching out to find spaces to fit, they gradually disappear within each other, and before you know it you’ve walked in one house and exited from a completely different one.

“Only In Dreams” is the technical side to the organic, oceanic surge of doomy drone that defines “Bodyless”. It’s the fluorescent bulb hanging in the world’s largest server room or the sound of signals broadcast through the fiber optic cables of our planet’s newly developed exoskeleton of information. Both songs are explorations of Broadrick’s sad, contemplative dark ambience, laying a foundation of organic versus synthetic, leaving open those invisible spaces. Like most great ambient, Broadrick has the patience to let the noise speak for itself, encouraging the listener to let the sonic membrane seal its connective tissue around them.

“Inbetween You”, the album’s centerpiece, revolves around a familiar Jesu-inspired stroke on the guitar, bent and distorted, twisted beyond recognition. Sounds interact in ways that add to the central resonance. There are hints of a train engine in the distance; the incessant basement hum of an industrial-sized climate control; the deafened throbs of an Airbus 380’s engines. If the first two songs were the yin and the yang of our human existence on this planet, then “Inbetween You” acts to bridge a connection between Earth as it is (and should be) and Earth as we want it to be (which isn’t necessarily a good thing). Shimmering notes that go in and out of frequency and rhythm act to connect the dreams to reality, an aural backdrop for the parts of life words can’t describe. It’s the sound, of course, of Broadrick searching for better terms.

If any of this sounds overly superfluous, you are probably right. Ambient and drone projects lend themselves to a different rubric of efficacy: as they evoke moods, it’s impossible not to describe them in such poetic (re: bougie) terms. One needs to understand that the goal of a drone/ambient album is to air-drop the listener into an experience that is shaped over time. No one is putting the penultimate song “Your Bit of Sky” on a mixed tape, but that doesn’t take away from its ability to add emotional heft to Broadrick’s soundtrack, a chance for the listener to exhale and take in the space around them.

It’s this emotional heft that gives the album its simple beauty. Brian Eno understood that the space within an airport resonated in such a way that nothing other than the songs on Ambient 1: Music For Airport would suffice to explain that space. William Basinski understood that the rift that left lower Manhattan shattered in 2001 could only be filled with the slow, sonic dismantlement and reestablishment of molecules on The Disintegration Loops. This is not to say Broadrick’s ambient work is up there with these two luminaries; however, like Basinski and Eno, Broadrick understands that the heart of the drone is the consistent evocation of feeling. He’s working to describe what we don’t see. After all, isn’t that the essence of the artist: explaining to the world what can’t be explained?

Justin Broadrick has spent the better part of the last four decades trying to explain what can’t be explained. While What We Don’t See doesn’t push the ambient envelope, by any standards, farther than it needs to go- Broadrick has made this same album many times- it’s a good place to start, in terms of finding a good fit for those spaces that need some filling up. As Final‘s simple drones file effortlessly into the sonic night, What We Don’t See fills that void with somber, contemplative energy. Broadrick’s lifelong quest to find the ‘better terms’ is one that gives a glimmer of hope on a planet that seems desperate to close its eyes to reality. Sometimes it’s what we don’t see that we have to fear the most.