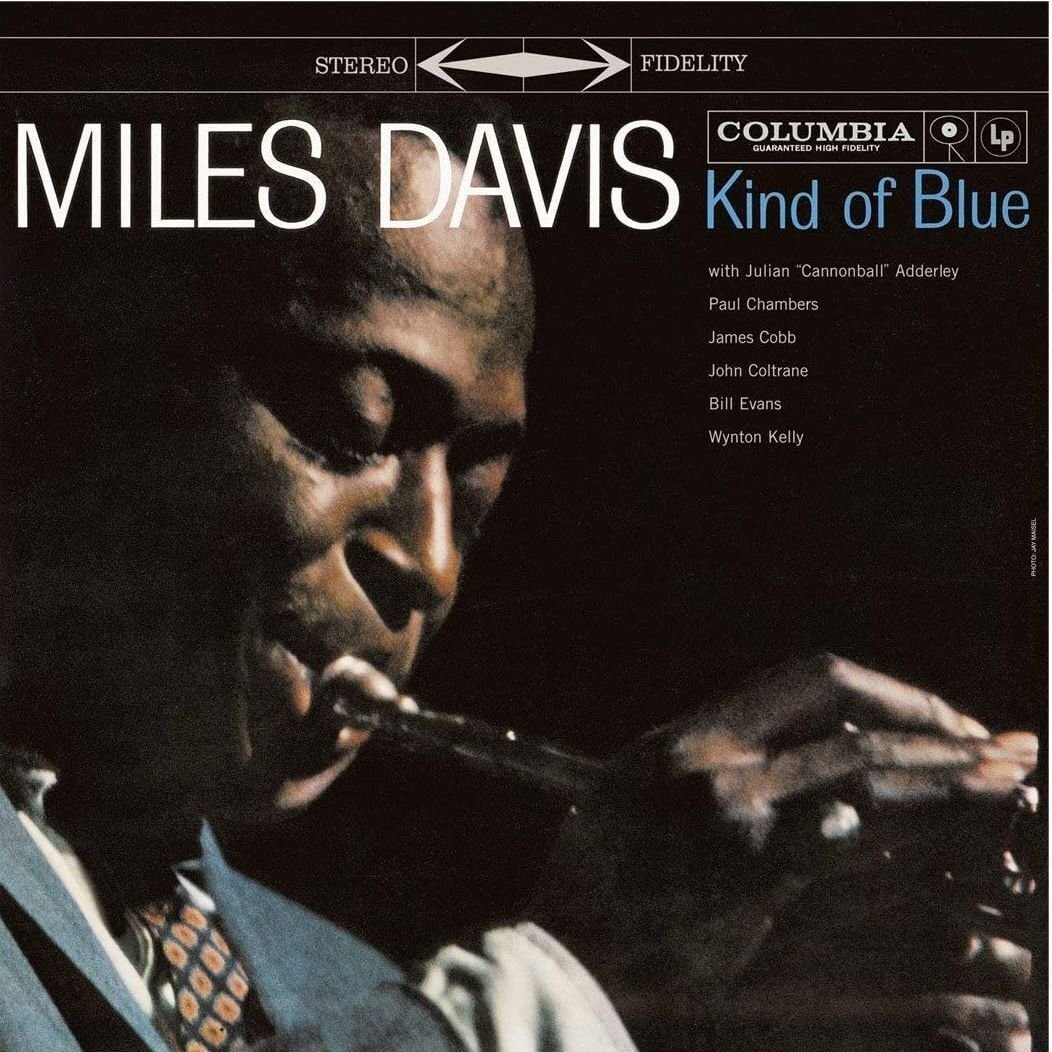

Release date: August 17, 1959 | Columbia Records | Website

Making a hypothetical Mount Rushmore of jazz without Miles Davis would be disingenuous and the most secular act of blasphemy one could ever seek to achieve. If there’s one man who constantly, ravenously sought to improve and re-invent himself and his music, it’s Davis. From straight-ahead bebop to interstellar fusion jazz, he has done it all, creating new styles and making a name for himself as a musician and an artist.

Kind of Blue saw the birth of his first genre offspring: modal jazz. He hinted at this quantum leap on previous records, but it’s here that it came into full swing (pun intended). This is the massive, solid foundation he would launch his later rise into the stratosphere from, the absolute bedrock of his current standing as a jazz legend. And as much as I love his electric period, I wouldn’t dare to deny the greatness of Kind of Blue, a near-perfect album in a genre overflowing with talent and creativity. The musicians, the songs, the art direction – everything about this record was (and arguably still is) on point.

Steve Loschi

In 1994, I lived in a two-story house on a double lot behind my university in Norfolk, Virginia. The houses on the street that ran parallel to the campus were older compared to the sprawling suburbs that encroached on the small naval town. Built in the ’30s and ’40s, most were in various states of disrepair and were populated by young kids and college students, including a couple of less than respectful frat houses. My roommates were a married couple who I’d met through our local music scene. We were a little older, people who’d cast their lot with the creatives that were exploding in the late ’80s and early ’90s until we realized that playing guitar in a goth band wouldn’t pay the bills, and the local school was right there. And so it was, I found myself a couple of years after punk broke, working the night shift at a local hospital and going to classes during the day. We were mature, damn it, no longer 20-year old kids but seasoned veterans of the dog-eat-dog world of rock and roll. Which brings us, of course, to the even wilder world of jazz, in which all roads end with a single artist, the incorrigible, magnificent, and brilliant Miles Davis.

Before we dive into the genius of Davis and the magic of Kind of Blue, however, we need to start from the beginning. As the resident grandpa of this esteemed Internet publication, I feel it’s my duty to educate those who grew up with phones in their hands and wireless controllers for their gaming systems on life in the pre-technology days, back when things were oh-so-gloriously analog. I mean, I had to put the world’s tiniest cassette tape into an answering machine and my controller was connected by a cord to my Super Nintendo system, for God’s sake.

So gather round all those who were raised on djent, and hear from a guy who would get in his car and drive down to the Planet Music to actually pay ten bucks to hear one single album. But to understand where we stand, we need to start with The Penguin Guide to Jazz on LP, CD, and Cassette, a veritable tome of a book I bought back then to start my journey into the dark, smoky corners of basement bars and swinging trios of stand-up basses, baby grand pianos, trumpets or saxophones. The Penguin Guide was exhaustive. Listed in alphabetical order, it was an analog version of AllMusic, seemingly containing every single jazz recording that had ever been pressed to vinyl. Even better, the contributors weren’t reticent to call a bad album a bad album, and would christen the must-haves with five-stars and a crown. And that’s where I started: with the crowns.

So I’d drive my piece of shit 1985 Plymouth Voyager that I inherited from my parents to the Planet Music with a scribbled list of albums on the back of a receipt and head in there, a man on a mission: to fill the shelves of my music castle with jazz royalty. I’m pretty sure the first album I bought was John Coltrane‘s A Love Supreme, a record my roommate and I played all the time as we sat in the laundry room doing shots of potato vodka after a night at the bar. That record is seared into my soul as the pinnacle of jazz, a metaphysical exploration of how music can transport us beyond the physical world and into something for which there are no words. Kind of Blue – for me-came on the heels of this album, but where Coltrane seemed to be having a conversation with God, Miles had feet that were firmly entrenched on the terra firma of the Earth. Charles Mingus‘s The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, Sonny Rollins‘s Saxophone Colossus, Dave Brubeck’s Take Five, all were on permanent rotation in that house on Melrose Parkway, just up the street from the old football field. But Kind of Blue just stuck, an adhesive monolith of adventurous, yet melodic jazz. It was music that seemed made for the reality of urban living – of concrete highways and towering skyscrapers, the sound of a subway train leaving the station, the steam pouring from a grate on the corner of an intersection, bodega windows filled with the necessities of daily life. Miles Davis understood the grind, and understood why we were all grinding it out. Kind of Blue was the soundtrack for holding a glass of scotch in one hand and a slowly smoking cigar in the other at the end of another long, shitty day at the nine-to-five.

There’s really no need to dissect each track on Kind of Blue, as they’ve all become standards in the world of jazz. I’ve heard popular artists talk about songs they’ve written that have reached such a pinnacle of cultural saturation (think “Seven Nation Army”, for instance) that they feel like they no longer belong to them, and that’s where Kind of Blue sits. It’s more than just a Miles Davis album: it’s an American album, and belongs to all of us. It’s hard to hear Miles, Coltrane, Cannonball, Evans, Chambers, and Cobb fall into unison on “So What” and not find yourself going ‘BAH DUM’ over the main motif. Likewise for the smooth melodic interplay between the band (sans Evans, who was replaced by Wynton Kelly on the track, whom Davis thought had a better feel for the blues) on “Freddie Freeloader”. And if you’re looking for the soundtrack to a down-on-his-luck detective and the femme fatale? Look no further than “Blue in Green”. It’s so on point that it’s hard to realize how damn revolutionary all of this was back in 1959. I mean, these songs feel like they’ve been part of the cultural landscape forever.

Listening to the album again, brings me back to those days in the mid-’90s, when I first started taking that deep dive into America’s greatest art form. That being said, Kind of Blue is one of those albums that’s never really left my deep rotation, and that thing’s been rotating for the better part of three decades. I can’t say that for a whole lot of albums, regardless of what art form they are missing. And while that paperback copy of The Penguin Guide is long gone and the building that housed Planet Music has gone from a Circuit City to a Bed, Bath and Beyond to a soulless suburban condominium, Miles Davis‘s trumpet still rings like a siren of America at her best, and we’re all a little bit better off because of it.

Broc Nelson

Kind of Blue by Miles Davis has long been on my rotating list of desert island albums. The opportunity to write a few words about this timeless album is too great to pass up. The problem with trying to say something about Kind of Blue is that so much has already been said about it. This album stands high in critics and the public eye as one of, if not the best jazz album of all time. Its reputation and legacy have been enunciated through the years by folks far more capable in their abilities to write about jazz than my wavering hyper-fixations could ever allow. So, I will wax about it from a personal perspective.

I wasn’t overly into jazz when I first heard Kind of Blue. I had listened to a compilation of Charlie Parker as well as an album of his with a string ensemble. I was familiar with and enjoyed Time Out by The Dave Brubeck Quartet. I already had the jazzy hip hop of Do You Want More?!!!??! by The Roots in heavy rotation, so I went to the used CD shop and found Kind of Blue. I was familiar with its prestige, and bought the copy. I didn’t listen right away, but threw it in my CD folder in my car.

I drove at the time, but my vision correction stopped allowing that liberty, but that isn’t the important part. I was 19 years old and working at the local cinemas. I clocked out around midnight to find a massive Midwest storm outside. I ran to my car through sheets of rain and regained my composure. I sloppily tried to smoke a cigarette through a cracked window and fumbled through my CD case to pick my drive home tunes. There it was, a rather plain looking red CD that matched Columbia Record’s vinyl centers, and I knew the rainy drive home was perfect for jazz.

I ejected Fall Out Boy or whatever was in the CD player at the time and popped in the disc. The gentle bass tones and piano chords of “So What” took me out of the parking lot and onto a mostly empty highway. As Davis’s trumpet and Adderley and Coltrane’s saxophones kicked in, the rain intensified, slowing driving down to a crawl. My 15-minute drive turned into a 30-minute journey through astigmatism streetlights and low visibility roads slicked from the torrent, each passing minute bringing new solos and meanderings through this effortlessly cool and sad sounding record.

The danger of the situation wasn’t lost on me, but I had never experienced such joy and exhilaration from foul weather soundtracked by music that seemed to be made for rainy streets. My cigarette had become hopelessly waterlogged from trying to ash out the cracked window, my armrest soaked and clothes still wet from the brief time outside. I thought, ‘to hell with it,’ and lit another. The slightly more up-tempo and swinging “Freddie Freeloader” started, and I was already transfixed. Each passing set of headlights seemed like another opportunity to collide with either driver’s slightest misstep, but somehow the romance of the setting and sound blasting from my stereo, loud enough to overpower the rain on my used Oldsmobile, gave me an absolutely unfounded confidence that everything was going to be ok.

As I approached my neighborhood, the downpour began to calm into a steady rain. “Blue In Green” started, and I heard the saddest-sounding trumpet I have ever heard. Bill Evans’s melancholy piano chords while Paul Chambers’s bass plucks wept tears bigger than the newly formed puddles in central Davenport, Iowa. As Evans and Davis played on, the tears from this track could have flooded the mighty Mississippi River just a mile downhill. It never ceases to amaze me how this combo of musicians managed to convey every sense of romantic loss and longing, every shade of malaise and existential query, and wrap it into the perfect record for introspection without a single word.

I pulled into my parking space in front of the house I was renting with my friend at the time. The lights were off, and I knew he was asleep. I kept the car on and let the shuffle of “All Blues” play. Now that I was safe and less tense, the weariness of a long day of college classes and a nightshift began to set in my body. Popcorn dust still managed to cling to parts of my skin and clothes where the rain hadn’t washed it away, yet I couldn’t bring myself to head inside for the shower and sleep I needed. Kind of Blue kept me glued to my seat. Inside was all tiptoes and quiet, but I had cigarettes to chain smoke and Coltrane’s solo halfway through “All Blues” is too good to ignore, even with the one weird off note.

“Flamenco Sketches” slowed things back down into the beautiful, poetic, and solitary sadness that Kind of Blue captures in a way that no other record really does. My eyes closed, and all I could do was listen. This was before smartphones, so I had no pressing social media serotonin addiction to re-up, nowhere to go but my thoughts which were laser focused on each note, each softly brushed cymbal that electrified my mind through whatever mixture of adrenaline and exhaustion was trying to bring me indoors. As the band played out, I finally went inside with an elegiac feeling that previously only Walt Whitman or Allen Ginsberg could invoke through their poetry. Music, up until that moment, had given me many thrills and some tugs at the heartstrings, but nothing had ever felt as literate as this instrumental record, before.

I don’t know how many times I’ve heard Kind of Blue since then. I know I have purchased it several times in various formats. I know that every time I hear “So What” my mind races back to that storm and the radium-green glow of the Oldsmobile’s digital dashboard. I know that with each listen of this album, I feel a strong connection to some kind of past life or at least the romance of one. Some smokey apartment where Neal Cassidy tells Jack Kerouac to throw this record on while Gary Snyder lets his meditation session be interrupted to enjoy this music, and I am a fly on the wall, or maybe some heartbroken transient private eye in a trench coat carrying a wad of small bills, a flask, and a single photo trying to piece together his life.

In reality, I am an elder millennial, struggling to survive unprecedented times, finding comfort in a loneliness I have to work too much to correct, letting each record and article fulfill some lost sense of adventure and youth, unsure of what comes next, but fulfilled with the knowledge that great works of art like Kind of Blue can provide some temporary transcendence, escapism, and comfort for the next rainy journey into the unknown night.

Joe McKenna

If you were to mention the title Kind of Blue, not just in jazz music circles but to anyone with even the broadest knowledge of music history, pretty much everyone would be able to appreciate this record’s profound influence and aura that is deemed an archetype for the future of music in the 20th century. Of course, the subjectivity in jazz music would often tell you that Kind of Blue has some competition to be one of the genre’s most complex, transcendent, diverse, and even modally incentive records to exist, even in Miles Davis’s discography alone; however, the cultural significance and historical value of this record has somewhat laid the fundamental backbone as to how such music is composed, performed, and analysed. As someone whose journey into jazz music has been a fairly new endeavour of mine, the music of Davis was of course a must to get me started. Further, my analysis of this record understanding the theoretical aspects of modal jazz and its derision form bebop (a style that I have come to be even more enthralled by), and exploring the work of each artist involved in the making of Kind of Blue provided me with a newfound aptitude that appreciates how such music is played and how it is accurately defined within the canon of modern popular music.

In the late 1950s, jazz music had become a staple of American culture. An appreciation of the style’s complex musicality that signified sophistication and artistic merit would be acknowledged on Broadway, in magazines, and even through some mainstream media outlets. Yet despite becoming engrained into the fabric of modern culture, many artists such as Charles Mingus, Dizzy Gillespie, and Ornette Coleman sought to take jazz in more musically challenging directions to no great recognition beyond the genre’s core spheres into wider public attention. For Miles Davis, this was however something of task that seemed to come naturally into fruition. The choice to bypass his previous explorations in bebop and focus primarily on utilising modal playing, as this appeared to be a clear component in allowing the artist to carve out jazz’s musical appear to a broader audience. The employment of some of the genre’s prized musicians further elevated the success of this record it seems with the additions of Bill Evans and Wynton Kelly on piano and John Coltrane on tenor saxophone, playing a vital role in shaping the modal harmonies and smooth transcendence that brought an inclusive appeal to many listeners. Whilst the rhythmic duties of bassist Paul Chambers and percussionist James Cobb would construct a dominant foundation for which experimentation would commence.

Kind of Blue, for me, is an album that obtains a certain kind of charm over time. The way the music is able to maintain its aura with each listen is something that dosen’t come around too frequently. I think what catches the ear so distinctly is the musicianship of each contributing artist, the chemistry was on point, and you get a glimpse into what the future would hold for some of these prominent musicians. I listened first to “All Blues” as a 17-year-old with absolutely no knowledge of jazz music, being instructed to transcribe that iconic opening phrase from saxophone to guitar may not have resonated with me as much so then, but those notes certainly such with me over time as my interest in this kind of music began to materialise. It’s only now that each listen allows me to pick out something new and ride with it for some time, the beauty of this record.

The deep expressiveness of Davis and Evans’s conversations in harmony on “Flamenco Sketches” are truly beautiful and emotional at their core, the warm and waning connotations within each melody is executed with well-timed flair and spontaneity. Chambers’ bass lines set are perfect at setting a distinct musical setting that don’t seek to prioritise the root note in order to expand on the band leader’s emphasis on modality and improvisation with vigour. Coltrane demonstrates his transcendental qualities through memorising improvisations on the track “Blue in Green” in a way that foreshadows the later career of the late great saxophonist. The subtle swing in Cobb’s drumming shouldn’t go without recognition; “Freddie Freeloader” for instance, is driven by Cobb’s composure and delicacy in his playing that opens a whole field for experimentation for the other musicians to explore.

These are all little fragments of musicality that I have picked up on all whilst listening just now as I write this piece for this feature. There are so many things parts to this album that intrigues, entertains, pleasures, and educates, partly due to its accessibility as a jazz album but also partly because Kind of Blue is able to communicate so thoroughly to the soul and resonate so deeply within the body and mind of the listener.

Toni Meese

Since my buddies here will probably tell you in detail why this album is great and deserves all the praise it has received over the decades, I decided to take a slightly different approach. Well, yes, in the end I will join in the praise and my verdict will be the same. Kind of Blue is one of those records you have to listen to at least once. But that would kill the suspense, right?

I want to talk about a phenomenon that has accompanied this album since I started listening to jazz. It’s the ultimate jazz poster boy. It’s the record that tops all the lists, the cover of which you’ve probably seen without having heard a note of the album. It gets thrown around in every sophisticated conversation about jazz – and in some ways it checks so many clichés about the genre that some first-time listeners will simply recognize it as the epitome of ‘ah yes, this is the sound I had in mind when I thought of jazz‘ – it comes up when you type jazz into Google.

And you know what, I’m with you. Kind of. Maybe I’m projecting a lot of my own experiences into this. Probably totally. When I got into jazz, I wasn’t that interested in looking at Miles Davis. Standard jazz, as I called it in my head, had nothing to do with me. I had skipped all the standard metal stuff when I was a teenager, why should I deal with the stuff that everybody means when they talk about jazz? The surface wasn’t that fascinating to me. Miles Davis was the kind of music that normal parents put on at dinner parties to show how sophisticated they were. Miles Davis was not art, it was a statement.

Little did my edgy teenage mind know. Sometimes things are universally acclaimed for a reason. And maybe it’s not the worst thing that one of those entry-level jazz records being recommended left and right everywhere you look is actually good. Outstanding, even. But why? It’s so influential – that’s what everyone says. It featured players who were becoming household names in their own right – Bill Evans, John Coltrane, basically the entire Miles Davis sextet. It shaped modal jazz like nothing else. And maybe all the praise, all the legacy, all the hollow words written by people who were just participating in a narrative that we all agreed upon doesn’t really matter. I know it’s almost impossible to look at art without context, especially art that’s so famous and legendary. But.

I really love “Blue In Green”. It made me discover and fall in love with the music of Bill Evans. It has magic, it makes me feel things, it makes time dissolve into irrelevance. Kind of Blue is a good album. The best ever, the pinnacle of jazz? Who cares. It’s good, and listening to it will probably make you smile and feel a little cooler.